In the last couple of weeks, there has been some discussion of large-scale real estate companies buying up single-family homes in order to rent them. Home ownership looms large in the American imagination and so this kind of news is met with lots of negative reactions as people sense that regular people are now competing with the capitalist class for the nation’s housing stock. At present these concerns are mostly overblown: the percentage of houses owned by single-family REITs and similar kinds of companies is still quite small. But everything starts small and so I suppose it’s not unreasonable to think that this is a harbinger of things to come.

As part of this discourse, many people said things about homeownership and renting that seem a bit mixed up about the financial differences between the two. And this is common in discussions of homeownership more generally. People seem to think that, when you go from a renter to a homeowner, all of that money you used to be paying in rent is now going towards home equity, which is to say going back into your own pocket, at least as far as net worth is concerned.

But this is not how it really works.

To see how the finances of homeownership actually play out, I decided to compile figures from my own owner-occupied home, which I purchased less than a year ago. My home situation is fairly conventional. I have a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage. I had to put down slightly more than the customary 20 percent for a down payment (only because the lender would not count my podcast income towards their affordability formula). But it was otherwise a very standard transaction that most homeowners would be familiar with.

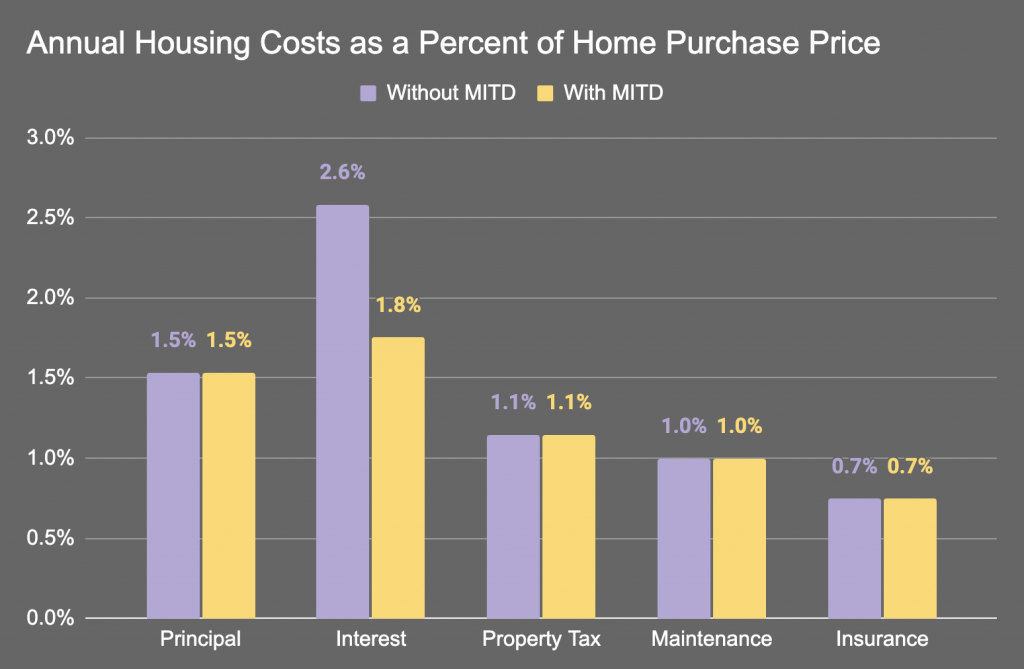

In the following graph, I break down annual housing costs by category. All the values are expressed as a percent of the home purchase price in order to make it more relatable to homes of different values and to make it easier to think about return on investment. The purple bar is without counting the Mortgage Interest Tax Deduction (MITD), a tax expenditure program that allows you to deduct mortgage interest from your income for federal income tax purposes. The yellow bar is with counting it.

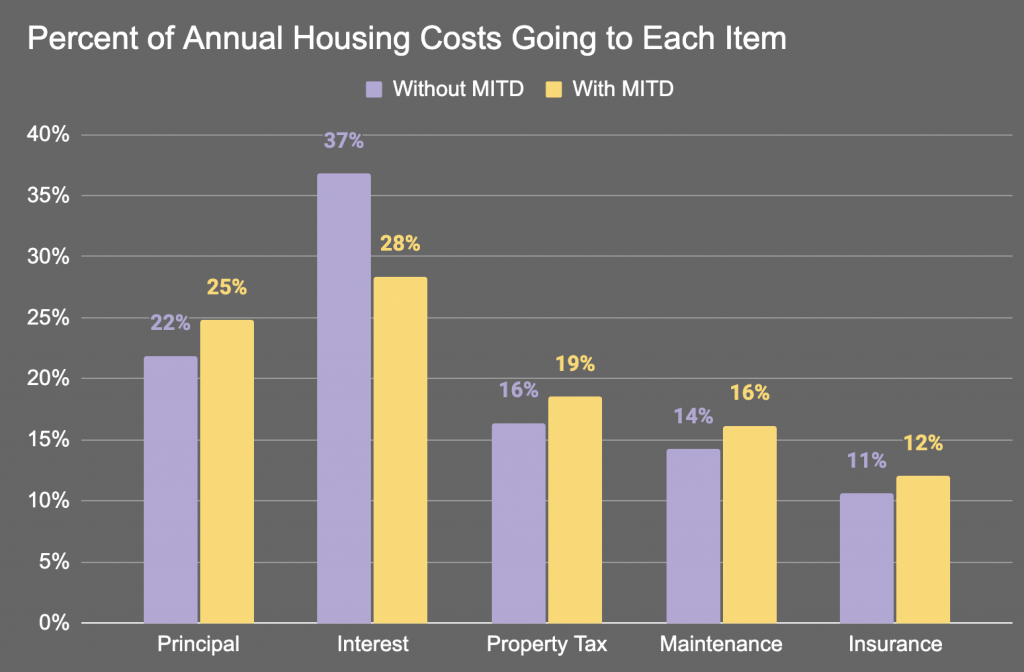

Interest, property tax, maintenance, and insurance are, from a personal finance perspective, indistinguishable from paying rent. Only the payments towards principal build net worth. Without counting the MITD, principal payments are 22 percent of the annual housing costs. With counting the MITD, they are 25 percent of annual housing costs. This means that 75 to 78 percent of the monthly housing costs are going, effectively, to rent.

Of course, to say that payments on principal are building net worth is also a bit misleading. It is not payments on principal that build net worth. It’s surplus income (including unrealized capital gains) that builds net worth. When you make a principal payment, you are taking net worth you already have in the form of cash in the bank and moving it over on the balance sheet to achieve lower indebtedness. That move, by itself, has no effect on net worth. It’s just reshuffling the balance sheet.

The investment return for doing this specific transaction is equal to the difference between the interest paid by your bank account and the interest rate on the mortgage. Ally Bank pays 0.5 percent interest for their savings accounts. After counting the MITD, my effective mortgage interest rate is 2.295 percent. So these principal payments are generating a net return of 1.795 percent (2.295 – 0.5). These same dollars, if placed in a diversified stock/bond portfolio, would generate a much higher return than that.

So if most of the annual housing payment is going to rent-like expenses and the principal payments are going towards a very low-yielding investment (paying off low-interest debt), then the main game in terms of building net worth is hoping that the price people are willing to pay for your home increases over time.

Betting on home value appreciation has paid off on average over time, but it’s definitely not a risk-free bet for any given property or over any given time period. Between 2000 and 2006, national home prices increased by 84 percent. Then, from that high, they tumbled 27 percent between 2006 and 2012. Depending on when you bought in and sold out, you could have experienced a lot of appreciation or a lot of depreciation.

Of course, not all homes rise and fall in value according to national averages. Some areas see housing prices skyrocket while others see them plummet.

Even if you luck out and your home’s price does rise, you now have to ask yourself: how exactly does this benefit you? If you continue to live in the home, this price appreciation is an interesting entry in your balance sheet, but you can’t spend it on anything. And if you sell your primary residence to access the appreciation, now you have to buy another house, which, if it is nearby, has also increased in price just like yours has, making the whole thing a wash.

In fact, it makes the whole thing worse than a wash because every time a house is sold, the buyers and sellers together pay about 8 to 10 percent of the home’s value in transaction costs to real estate agents, the government, and other similar parties.

To really benefit from home value appreciation, you need to sell your home and then move to somewhere that homes are much cheaper, like New York retirees who sell off their NYC real estate and head to Florida. Short of that, you could sell your home and then rent in your area. Assuming home prices and rents are related to one another, this is not a financial win over the long run, but if you’ve only got a few years left to live, the long run may not matter and you can use the cash to pay for other expenses.

Beyond the personal finance aspects of home value appreciation, there are, of course, the political aspects of it. Home prices often rise due to unsavory decisions to restrict the housing supply, which causes serious financial problems for others, homelessness, and other similar maladies. If your area’s housing stock is keeping up with local housing needs, your home probably won’t increase in value. Banking on home price increases as your engine of wealth accumulation is mostly just banking on future housing shortages.

So, the financial case for homeownership is much weaker than I think most realize, especially when compared to alternative ways of investing the same money. And to the extent that the financial case exists, it is largely tied up in tax benefits — mortgage interest tax deduction (MITD), capital gains tax exclusion for home sales, non-taxability of imputed rent, and the state and local tax (SALT) deduction — not homeownership per se.

These tax benefits have also been heavily scaled back in recent years. SALT was capped at $10,000, which is mostly or entirely gobbled up by state income and sales tax for many (most?) homebuyers, meaning that there is little to no marginal federal tax relief for property taxes. The MITD was not scaled back for regular homeowners, but the standard deduction increased so much that claiming the MITD no longer makes sense for many (most?) regular homeowners and, even where it does make sense, the marginal relief from claiming the MITD over the standard deduction is relatively small.

I say all of this, not to shit on homeownership, but just because I think a lot of people’s understanding of it is very overblown, at least as far as finances go. Homeownership has been the centerpiece of middle class wealth because that’s where the middle class put their money, not because there is something special about leveraged owner-occupied real estate investments as an asset class. If the middle class put their money in bonds or stock, including by buying shares of single-family REIT companies, then that could also be the centerpiece of middle class wealth.