In my previous post, I argued that it was misleading to represent the issues of recent college graduates (e.g. student debt) as the issues of the younger generation. I pieced together some rough data from the Census and the National Center for Education Statistics that tended to show that the majority of youth are not recent graduates and that a non-trivial number of recent graduates are not youth.

Mike Konczal linked me to a post he put out last November breaking down the distributional impact of student debt. Overall, this data supports the two main points of my previous post, and indeed other arguments I have been making in the past few weeks.

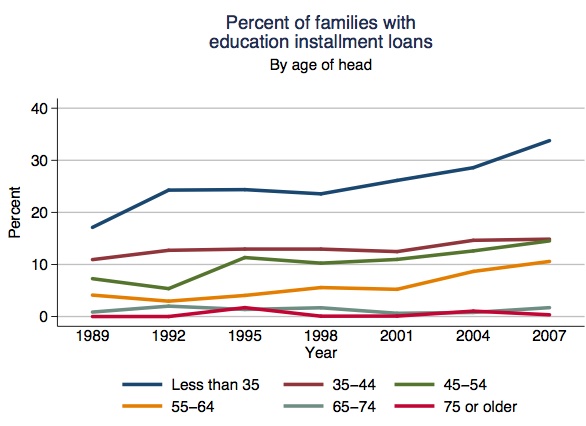

The overwhelming majority of the younger generation do not have student loans. In 2007, only 33% of those below the age of 35 had student debt, meaning of course that 2/3rds of those under 35 did not.

Notice also in the above graph that there are a substantial number of people with student debt who are not in the younger generation. Around 15% of people in the 35-44 and 45-54 age bracket have student debt, and slightly more than 10% of those in the 55-64 age bracket have student debt. We would expect a higher percentage of those below 35 to have student debt because they have had less time to pay back their debt and because educational attainment has been increasing.

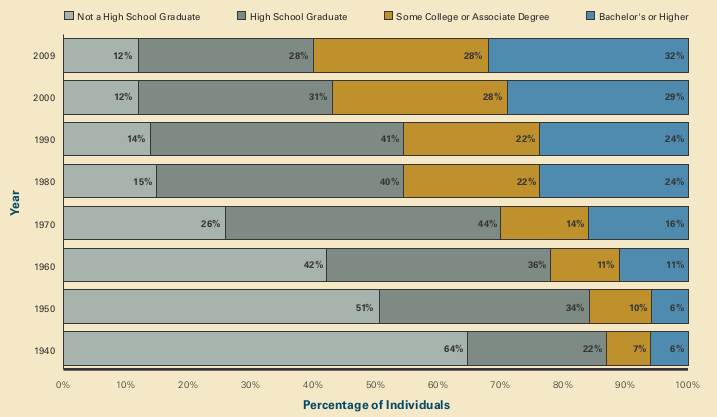

In 1990, 46% of the population had some college or higher, while in 2009, 60% of the population had some college or higher. Although rising tuition definitely plays a role in student indebtedness, it is also true that an increase in educational attainment will generally entail an increase in the percentage of people with student debt. Rising student debt then is partially a sign of a good thing: rising educational attainment.

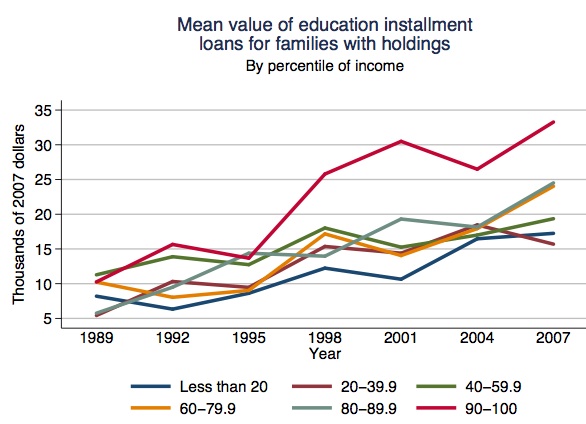

When we look at the average amount of student debt by income distribution, we find that those with the highest student debt also have the highest incomes. The top 10% of income-earners have the highest average debt at around $34,000; the next 30% of income-earners have the second highest average debt at just under $25,000. And so on:

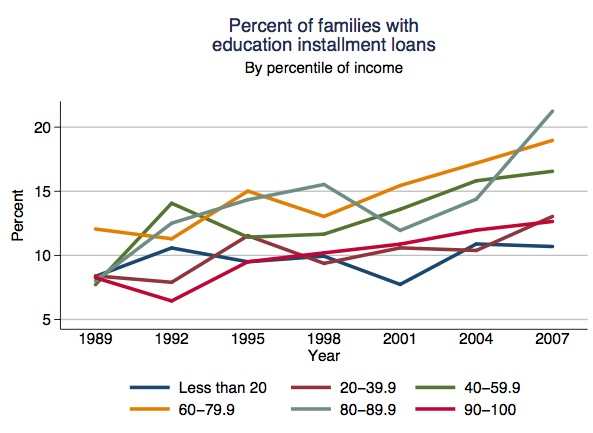

This is entirely predictable because professional degree holders have the highest debt and make the highest incomes. When we look at what kinds of families have any student debt at all, we find that the richest and poorest families are the least likely to have student debt, while families in the 40-90% income percentile are the most likely to have such debt. But even then, only 16-22% of those families have any student debt.

So after that flurry of graphs and data, what is the takeaway? First, the overwhelming majority of young people do not have student debt, and a significant chunk of those with student debt are not young people. As such, I think it is misleading to equate student issues with youth issues. Second, the highest percentage of households with student debt tend to be middle-to-higher income (in the 40-90% income percentile), and those with the most student debt have the highest incomes. In all of this, it also important to remember that college graduates as a whole come from relatively affluent backgrounds, have relatively affluent futures, and enjoy other economic privileges over their non-degreed counterparts.

I am sympathetic to the elimination of debt-financed education, and I have proposed an alternative income-based repayment system that I think is better. However, being opposed to debt-financed education is not the same thing as believing that the student debt issue is a class or generational justice issue. Those advocating for student debt relief and tax-funded, free college are also inadvertently advocating for redistributing money to the relatively affluent and for increasing overall economic inequality.