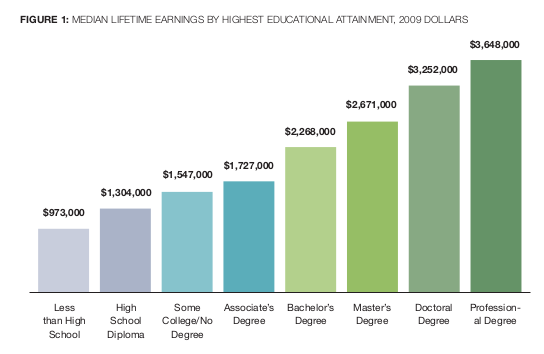

The New York Federal Reserve Bank released an impressive amount of research earlier this month on the present state of student debt. Total student debt levels are around $870 billion. Average student debt stands at $23,300, but the median debt — a more telling figure — stands at $12,800. At the same time, those with bachelor’s degrees make around $1 million more in their lifetime than those with only high school education.

These aggregate statistics can leave out some of the real strain many students suffer: some have debts 10x or more the median and enter jobs and careers with a much smaller college wage premium. But in general, the 30% of Americans with bachelor’s degrees occupy a very lucrative and elevated position in society and the economy.

These numbers make student protests about debt and tuition a bit confusing. The $870 billion student debt level certainly seems quite high, but it is spread out among 37 million borrowers. The occasional hysteria about student debt being the next bubble is, as Dean Baker put it recently, nonsense. That is not to say student debt is a total non-issue. As with most economic things, it tends to hurt people from poor backgrounds more than those from wealthier backgrounds. So there is an economic justice issue at play.

However, the usual class analysis approach is somewhat muddied in the case of student debt by the college wage premium. You can think of poor students as poor students or you can think of them as students that are soon to be doing, on average, pretty well. Poor students fall into both of those categories, which makes the class-focused approach to student debt complicated. Supposing that we did want to change the current higher education financing system to eliminate or reform the role of student debt, how exactly would we do that?

The first and most blunt option is to have the federal government pay for college directly from general tax revenue. As Mike Konczal pointed out, the federal government already heavily subsidizes higher education via tax deductions of various sorts. When these various subsidies are added together, they come very close to the amount of money that would be required to simply pay every college student’s tuition upfront. Thus, we could eliminate the higher education subsidies and redirect the money towards direct tuition payments.

But what would the distributional impact of such a policy actually be? First, as already mentioned above, we would be basically redistributing money to a class of people that stands to make a significantly higher amount of money than the population in general. Second, in Tier 1 universities, which are the most expensive, 74 percent of the students come from the richest quarter of households, while only 3 percent come from the poorest quarter of households. So if the federal government were to pay for tuition directly, the net effect would be a windfall for wealthy families who would be relieved from paying high tuition. It would eliminate the debt burdens of poor students too, but it would disproportionately direct money to students from well-off backgrounds.

To avoid simply handing enormous sums of money to wealthy kids, the second option is to use means-testing to distribute money. This option, like anything else that might be proposed, falls prey to the objection once again that even though poor students are currently poor, that they are in college generally means they have better times ahead of them. But if we ignore that, we certainly could decrease the burden on poor students by expanding Pell Grants or through other means. While I support such measures, it is important that we ensure the tax revenue comes primarily from wealthier individuals. Otherwise, you end up taxing poor working people who do not go to college in order to pay for poor students that are on track to make a significant amount of money.

The final option I will consider here is — I think — the best one, and one which some other countries rely on. We could make education free by levying a surcharge tax on everyone with a college degree. Under such a system, all college is free at the point of delivery, but all those who graduate are made to pay an extra 5% of their income, or some other amount, for the rest of their lives. This seems to have precisely the distributive impact one would desire. It eliminates student debt altogether; it taxes those who have benefited from college education to pay for the higher education system; it does not tax money from the 70% of people without a college degree; and, it ensures that those who benefit most from their college degrees — as measured by income — pay the most back into the system.

In the realm of economic justice issues plaguing this country, student debt is not even in the top 50. Students, regardless of their economic background, are on track to do way better than non-students. Most discussion around this topic tends to start from a bad analysis of what the student debt problem exactly is, and then proceeds to an even worse analysis about how to solve it. I am sympathetic to the idea of eliminating student debt altogether, but those who want to do it need to put together a serious and comprehensive plan that takes into consideration the actual class composition of higher education. The class composition of higher education skews rich, and if you get into the business of handing out money to students, you also get into the business of giving money to rich people who do not need it.

The only comprehensive scheme that I know of which addresses all of these class complications and simultaneously eliminates student debt is the final option presented above. It is hard to imagine such a reform being politically practical in the United States and the reform poses certain transition difficulties. Nonetheless, it is something worth working towards that does more than just pay lip service to the exaggerated and overblown issue of student indebtedness.