If you’ve read any think pieces about higher education recently, you are familiar with the accepted narrative by now. Back in the day — which usually means the 1970s or thereabouts — college was accessible to all and therefore an engine of social mobility and egalitarianism. But now things have changed. Higher tuition, student debt, and other sorts of neoliberalism have generated huge class inequities in higher education, closing it off to all but the very rich. This story is wrong. While it is true that higher education is primarily a rich kids’ game, it has always been a rich kids’ game and things are actually slightly more class diverse now than they used to be.

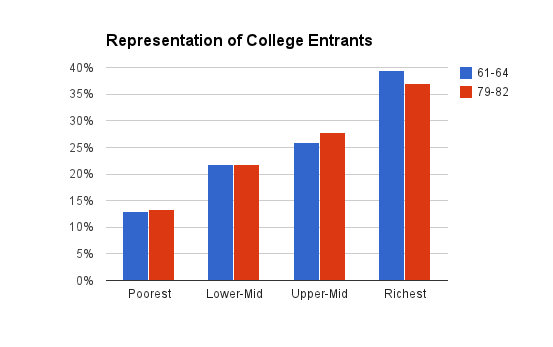

In a chapter of Whither Opportunity, Martha Bailey and Susan Dynarski compared the college attendance and completion rates of those born between 1961-1964 and those born between 1979-1982 using BLS data. This research was featured in part of a New York Times piece in December. From those numbers, we can figure out what percent of all college entrants and graduates come from each economic quartile, and how that has changed over time. Here is the change over time for college entrants:

As you can see, things did not change very much between the 1961-1964 cohort and the 1979-1982 cohort. The percentage of college entrants coming from each economic quartile remained fairly flat. The only difference is that the percentage of seats going to the richest quartile has declined while the percentage of seats going go the poorest and upper-middle quartile has increased. So, even if slightly, the class composition of the set of people called “college entrants” is less tilted towards the rich than it once was. A similar trend is found among college graduates:

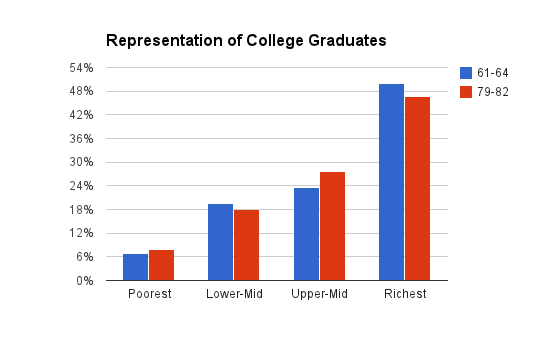

The percentage of college graduates coming from the richest and lower-middle quartiles decreased while the percentage of college graduates coming from the poorest and upper-middle quartiles increased. I am not totally sure if you would call this increasing class diversity or not. There are more poor and less rich, which is what I tend to be interested in. But the percentage of seats going to the two middle quartiles shifted to the upper-middle class, which is less egalitarian. That quibble aside, the real takeaway here is that things haven’t really changed in the 20 years between these two cohorts, not much at least. If we are going to say anything about the trend, it is that apparently higher education is more poor-friendly than it used to be, this running opposite to the accepted story.

Don’t get me wrong here: I think college is an institution primarily for the economically privileged kids in society. The data back that up, especially when we look at the best colleges in the country. But in noting that, we should not assume that it once was much more egalitarian than it is now. That is simply wrong, and people really should stop saying it. Not only is it false, it is not even that important to the argument. Those upset at the higher education status quo can certainly put forward strong arguments to support their grievances without this nonsense story.

Update: I want to clarify something. The data here is for two sets of people, those born between 1961-1964 and those born between 1979-1982. To count as having entered college in this study, individuals need to be in college by age 19. So for the first set, that means entering into college by 1980-1983. For the second set, that means entering into college by 1998-2001. To count as having graduated college in this study, individuals need to have a bachelor’s degree by age 25. So for the first set, that means having a degree by 1986-1989. For the second set, that means having a degree by 2004-2007. So the first set should be understood as reflecting the plight of traditional students in the late 1970s and early 1980s, while the second set should be understood as reflecting the plight of traditional students in the late 1990s and early 2000s.