Over at Slow Boring, Matt Yglesias argues that meritocracy is real but bad. Yglesias contrasts his take with the conventional position that is presented as anti-meritocracy but actually just argues that we don’t live in a meritocracy.

Here’s Yglesias:

And if you talk to people with a curious and open mind, you’ll pretty quickly find out that New York Times reporters are really smart. So are McKinsey consultants. So are the people working at successful hedge funds. So are Ivy League professors. Probably the smartest person I know was in a great grad program in the humanities, couldn’t quite get a tenure track job because of timing and the generally lousing job market in academia, and wound up with a job in finance at a firm that is famous for hiring really smart people with unorthodox backgrounds. Our society is great at identifying smart people and giving them important or lucrative jobs.

I’ve personally been less impressed in these kinds of conversations, but I don’t want to pick an irresolvable fight based on these kinds of impressions.

The actual question in this debate is not whether we do or don’t live in a meritocracy, but rather: how meritocratic are we? Are we a little bit meritocratic, very meritocratic, or somewhere in between?

To evaluate this extent-of-meritocracy question, what you would want to do is line up the population in order from the most merit to the least merit and then see how well that order lines up with the order of positions received. Are those with the most merit in the top positions and those with the least merit in the bottom? How much does the merit distribution deviate from the positions-received distribution?

This way of measuring the level of meritocracy is conceptually straightforward, but obviously in practice quite difficult. Definitions of merit vary. Definitions of top positions vary. And then actually collecting data on any given definition is difficult or impossible.

The one area where these kinds of definitional and measurement difficulties are able to be plausibly overcome is in college admissions. Student merit can be ranked by SAT and ACT scores and positions-received (college of enrollment) can be ranked by college rankings.

Chetty and friends did all of this in February of last year, with a focus on who enrolls in the most elite schools in the country, which he defines as Ivy League schools plus Chicago, Stanford, MIT, and Duke.

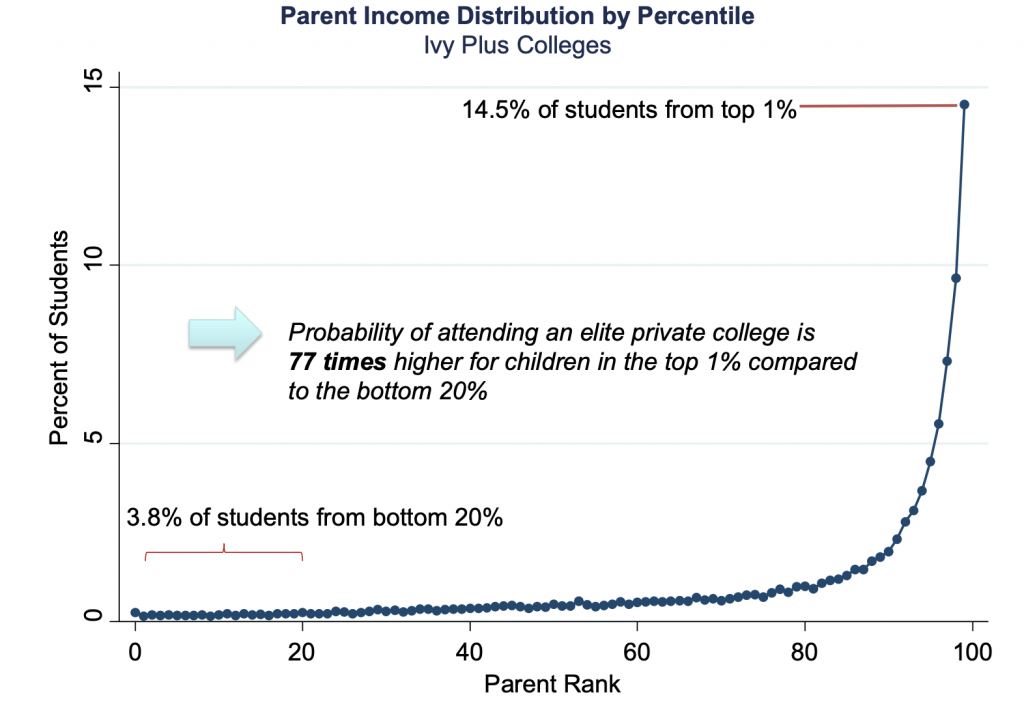

Overall these Ivy Plus schools are overwhelmingly skewed towards the children of the very rich.

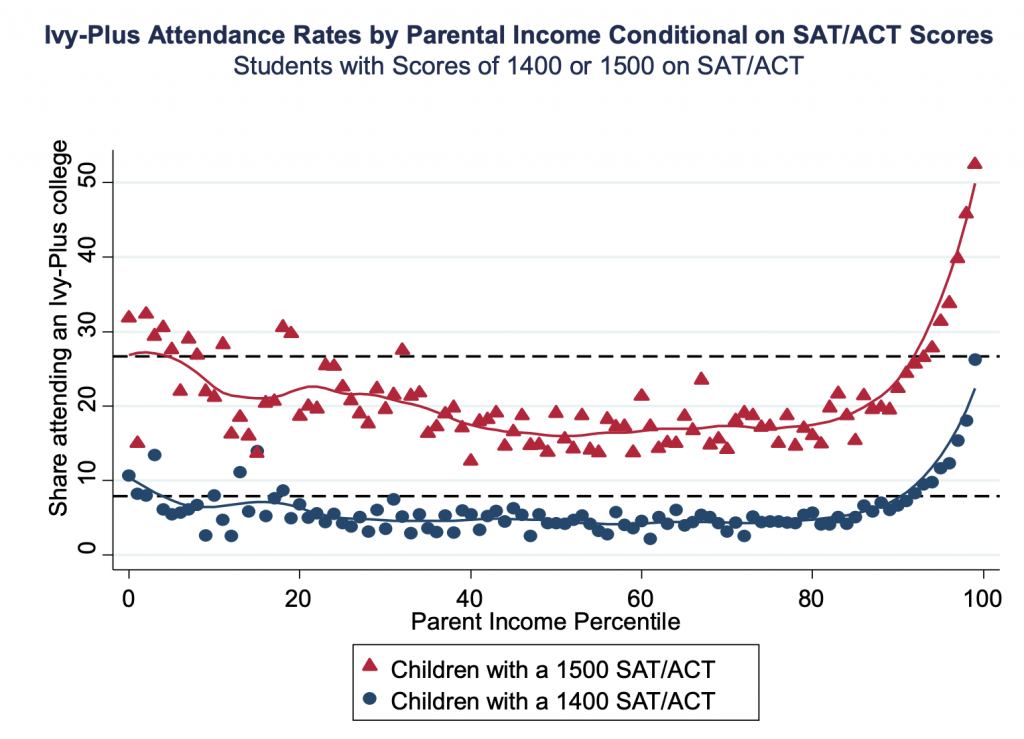

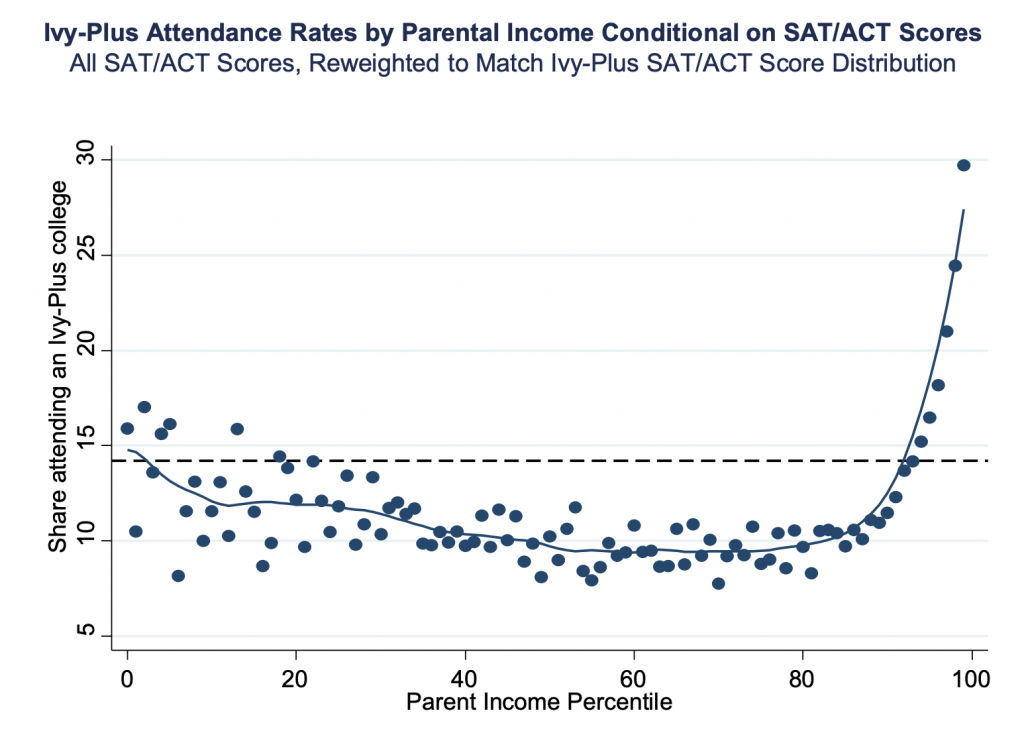

Freddie deBoer will correctly tell you that graphs like these don’t really settle the question because more affluent kids probably do have more “merit” (defined as academic ability at age 19 as measured by SAT/ACT scores) than poorer kids have. To really get to the heart of the question, we need to see what the odds of attending one of these schools is conditional upon SAT and ACT scores.

Chetty delivers that as well.

In a meritocratic world, the dots would all line up on the dashed line. Instead, we see quite a significant deviation from that, most notably at the very top: the richest one percent of kids are twice as likely to attend an Ivy Plus school even after you have controlled for differences in underlying merit.

I would assume similar dynamics operate in many areas of society. This does not mean that people in the top positions are, on average, mediocre when it comes to merit (however defined). But it does mean that there are plenty of people in those positions who are relatively mediocre. And this does seem to undermine the case for the current system even within a pro-meritocracy framework.

Although I somewhat disagree with Yglesias on whether meritocracy is real, I think we are on the same page when it comes to whether meritocracy is bad. In many cases it is and this is especially true when it comes to distributing income and wealth based on merit.

Economic justice, as I see it, is not primarily achieved by making the distribution of merit and the distribution of positions-received line up perfectly. Instead, it is achieved by compressing the differences between social positions. The goal is not to get the exact right students into Ivy Plus schools. The goal is to make it so that getting into those schools doesn’t really matter.