I’ve never seen someone get as thumped as Sumner in this weird exchange (him, me, him, me, him). It’s gotten a bit complicated now, as he’s shifted his position so many times. So it’s probably easiest to start with the certain victories.

First, Sumner has had two opportunities to respond to the fact that my market poverty rate (which he criticizes) is able to be arrived at almost purely through transfer programs that cut elderly and disabled poverty (which he says are exceptions to the usual rule that transfers can’t cut poverty). When Sumner wrote his first wandering piece, he starts it by saying I am way off by saying transfers cut official poverty by around 27 million people because of dynamic effects. Then later on, he said elderly and disabled people are exceptions and can be brought out by transfers. I pointed out that 20 million of the 27 million brought out by transfers are elderly and disabled, and so the exceptional populations alone get me to the market poverty rate conclusion he is trying to criticize (by the way, it’s actually 24 million out of the 27 million if you include people who are living with the elderly and disabled people).

I gave him two chances to respond to this. I actually tell him he is specifically not responding to this. But he never does respond. This is because he lost this point, and this was what the entire Grandpa Sumner beef was about, at least initially. He’s also just broadly dishonest as a person.

Second, Sumner has no idea how wealth data in this country work. I give three examples of him blaming it on life-cycle effects when in fact inequality within age groups is higher than inequality across the entire society. All he does is say he didn’t mean that was the only thing going on. But that’s not a relevant response. When critiquing wealth inequality magnitudes, it is an irrelevant point to talk about age when age-controlled magnitudes are as bad as overall magnitudes or even worse. Sumner also continues to have no response to the point that he says made-up shit like wealth data doesn’t include housing wealth when it absolutely does. No response. I bring this up only because it’s broadly emblematic of the Grandpa way he argues, where he just makes up shit because he doesn’t know what he is talking about and can’t be bothered to find out. Then, when pushed on it, he just runs away on to other subjects.

Beyond these points (especially the first one, which is what the whole shebang was about), all that’s left to do is clean it up.

The U.S. poverty data starts in 1967. Let’s retrace. Sumner said the War On Poverty was a failure. I pointed out that it wasn’t because it fell by 38% in the period that it was going on, and all of was attributable to transfer incomes. Sumner then changed his argument and said that, be that as it may, it doesn’t tell us anything because we need to know about poverty falling from 1922 to 1967. He further said that progressives (he never names anyone) keep saying poverty fell way down between 1922 and 1967. I noted that this would be quite a hilarious thing for them to say since the poverty metric wasn’t conjured up until 1964 and good data wasn’t collected on it until 1967. Sumner was finally coaxed to google and he found a website that had the line going back to 1959, which shows I am wrong.

Of course, observant people will realize that he said progressives tell him all the time poverty fell a lot between 1922 and 1967. But, assuming the poverty data we have only goes back to 1959 (as he now believes), how were progressives talking to him about 1922 to 1959? Where on earth did that come from? He made it up. He’s Grandpa Sumner. Alas, the 1959 data is not good data anyways. After the poverty metric got put in place, they ran it back a few years to 1963 initially. That was alright as far as things go, but the data is not great. Then, they had one tape from many years ago (not each year, just one of them) hanging out in 1959 with data that was not very good or collected with poverty calculation in mind. I can’t speak to how good that tape is because I don’t even know that it exists and alas can’t view it. But what I read tells me that it’s not taken seriously for these purposes even though you can still download Census spreadsheets with that year in it.

Comparative Poverty Analysis

For the last section, I figured I’d go with a bolded subhead because it is important. Recall, Sumner has no idea what he is talking about on any of this. He likes to tell a story about how he was a freshman and outsmarted his professor on this subject (which is the usual old man lore, not to be taken seriously in any case) because his understanding of this stuff literally never progressed past That Guy (you know who I mean) in the freshman undergraduate course. He never looked into it again.

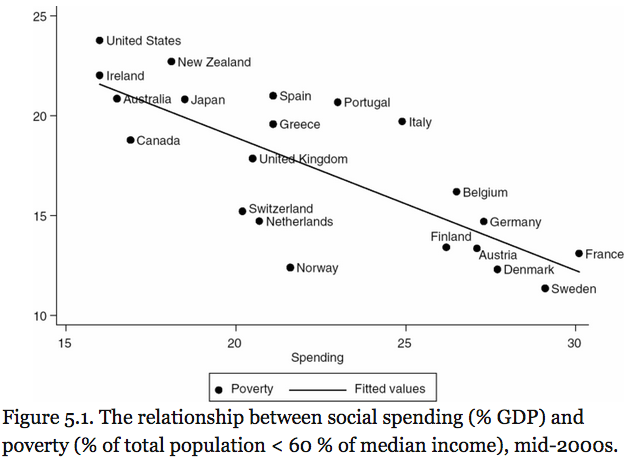

In my last piece, I included this graph to show that you can identify disposable income poverty effects without determining the spread between market income poverty and disposable income poverty:

Here’s Sumner’s response:

He defines poverty as making less than 60% of median income. Then he argues there’s more poverty in countries with less redistribution. What a shock! So let’s see, if Cambodia does so much redistribution that the incentive to produce food falls to zero, and median per capita income falls to 25% above starvation level, then by definition Cambodia would have no poverty. After all, you would starve with only 60% of the median income, so the poor would not exist. Pol Pot produced one of the world’s most effective anti-poverty programs! According to Matt’s graph, the US has more poverty than Greece or Portugal (in 2005). If instead you look at actual living standards (square footage of living space for the poor, car ownership, home appliances, Medicaid, free public education, etc.), then the poor in the US don’t do so bad, even when compared to the richer European welfare states. But the poverty experts don’t want to eliminate poverty—what would they do then?

When freshman Sumner brings this up in his freshman class, the professor would first address Cambodia. He’s say “ah excellent point Scotty boy, it would be hard for this measure to be applied in country at different stages of development. Do you notice something about the collection of countries here?” At which point Sumner would have probably been like “LOL professors are dumb, I am right, I am smarter than all my professors.” Then the professor would have said “well, no, what they do here is pick a collection of rich developed countries that are at the technological frontier, to avoid precisely this issue.” Sumner would have then blocked this out and told his friends for the rest of his life how he owned his professor and disproved all poverty research as a freshman that one time.

From there, the professor would explain why relative measures among rich, developed countries (even those with significantly different amounts of overall national income) make sense for this question. We use relative incomes because, assuming we pick similarly developed countries, it allows us to compare countries that have different capacities for generating income. The Nordic country of Norway, for instance, absolutely dominates everyone on that list right there in per-capita income. But its dominance in absolute income is a function of the fact that it is extremely natural resource rich. This does not tell us about the effectiveness of its institutions. Trying to compare the effects of institutions across countries with different capacities for generating per-capita income does not work unless you use relative measures because you can’t tease out what is owing to institutions and what is owing to different income-generating capacities.

The 60% measure here is one that the EU uses for its internal comparisons. And there is a very good question to ask here: why do some developed countries (regardless of their capacity to generate income or their labor/leisure choices) manage to get far more of their people closer to the median income than others? What is going on here? You can get at that question by regressing like I have in the graph above, which tends to show social expenditures (which include transfers, welfare benefits like health care, and schooling and such) are the key. You can also get at the question by comparing market income poverty rates and disposable income poverty rates, which generates a substantially similar graph as above.

Finally, you can get at them by creating a typology of countries based on institutional forms. The normal typology lumps the Anglo countries together under the heading “Liberal Institutions,” the continental countries under the heading “Conservative/Continental Institutions” (conservative coming, I believe, from their Christian Democratic and Catholic traditions) and the Nordics under the heading “Social Democratic Institutions.” This typology comes from tracking their political development and seeing which parties controlled government over certain periods. Anyways, that typology also mirrors the other two conclusions: Social Democratic Institutions beat Conservative/Continental Institutions, which beat Liberal Institutions (beat meaning does better on social indicators and inequality).

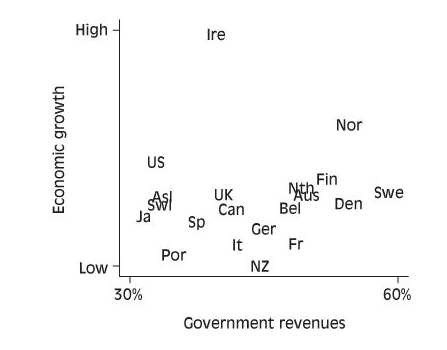

The proper worry to raise here (which Sumner appears to be reaching for, but doesn’t quite get to) is that these countries are accomplishing this lower relative poverty at the expense of growth, and so down the line they will actually fare worse. This is the Okun dance. But is it so? No. Here is growth and government revenue as a percentage of GDP from 1979 to 2007 (via Kenworthy, the best comparativist living right now):

Can you spot the trend where growth is falling down in the big social expenditure countries (note the four on the far right are the Nordic states)? Probably not because it doesn’t happen. In fact, the biggest comparativist study to date on this question found that higher inequality-reducing transfers are associated with higher growth, this from the IMF.

So if these countries grow at the same rate as we do and have less low-end inequality, put 2 and 2 together and figure out what that means for poverty.

Once again, Sumner is just out of his element on all of this stuff. As some folks on Twitter have said, it’s kind of sad to watch him float off into no-man’s land away from the only thing he has interesting, competent things to say on, which is monetary policy.