In late 2021, I had solar panels installed onto the roof of my house. After some bureaucratic delays, the solar panels began producing electricity for me at the beginning of January 2022. I have been tracking the performance of the panels for the last year in order to assess what the financial impact of the panels is for my household. This is mostly due to my own curiosity but also because I think the information could be useful to other people.

Acquiring Solar Panels

Getting solar panels on your house is a complicated process. You have to buy the panels as well as a solar inverter that allows you to make use of the electricity produced by the panels. You have to get someone to install all of this and make sure that it will work with your existing electrical system. In most cases, you’ll need to get permission and cooperation from the electric utility as well as local permitting authorities.

This is too difficult for most people to coordinate themselves and so, for the most part, it makes more sense to just contract with a solar company that will manage all of this for you. Sunrun is the biggest company that does this in the US right now. Companies like Sunrun will assess the solar-worthiness of your roof and then sell you a solar system based on that assessment. From there, they take care of all of the contracting with installers and electricians as well as all of the bureaucratic hassles.

Financing Solar Panels

There are three main ways of financing the purchase of solar panels:

- Cash.

- Solar Loan.

- Solar Lease, aka Power Purchasing Agreement (PPA).

Based on my research and my own experiences, you should avoid using a solar lease.

The way a solar lease works is that some other company retains ownership over the panels and then you pay that company a certain amount of money for every kilowatt-hour (kWh) that the panels produce. This is presented as a very attractive option because it de-risks the solar panel acquisition: the per-kWh rate is set below your existing electricity rates and, if the panels don’t produce, you don’t pay.

But solar lease contracts generally increase how much you pay for each kWh by two percent each year. They will tell you that this is no big deal because regular electricity prices typically increase by more than two percent each year, so your savings continue to grow. But once you do the math on the compounding two percent interest, you come to see that the solar lease costs massively more money over the lifetime of the panels than a solar loan or buying the panels outright.

Additionally, solar leases end up creating headaches if you ever need to sell your home, as the buyer has to take over the lease in order to purchase your home, something many are reluctant to do.

In my own experience, the first solar company I was working with was very aggressive about having me finance my purchase with a solar lease. Their initial sales pitch seemed reasonable enough, but once I looked into it, I became unsure that this was a good financing option. In an effort to see how much of a scam this might be, I told the sales representative at one point that I was thinking about just buying the panels with cash. This was not true as I did not have enough cash to do that, but in every other big purchase you make, offering to buy in cash generally causes the salesperson to perk up because that’s much easier and immediate than going through financing. In this case, the salesperson reacted very negatively and tried to talk me out of it, at which point I was quite sure the solar lease was a scam and I moved on to a different solar company.

If you are going to buy solar panels, either use cash or a fixed-rate solar loan. Do not use a solar lease.

My System

I ended up getting a 7.56 kW solar panel system consisting of 21 LONGi panels and 1 Solar Edge inverter. I did not really select any of this and I can’t say that I really know anything about different kinds of panels or inverters. The solar company did an assessment of my house and told me this is what I should get. So I did.

According to the company, the estimated 20-year output of these panels is 193,545 kWh. Twenty years appears to be the standard timeframe used to talk about a solar panel’s lifetime, though it doesn’t look like the panels actually cease to work after 20 years. It’s just that the amount of electricity they produce becomes significantly reduced by then due to wear and tear.

Electricity Production

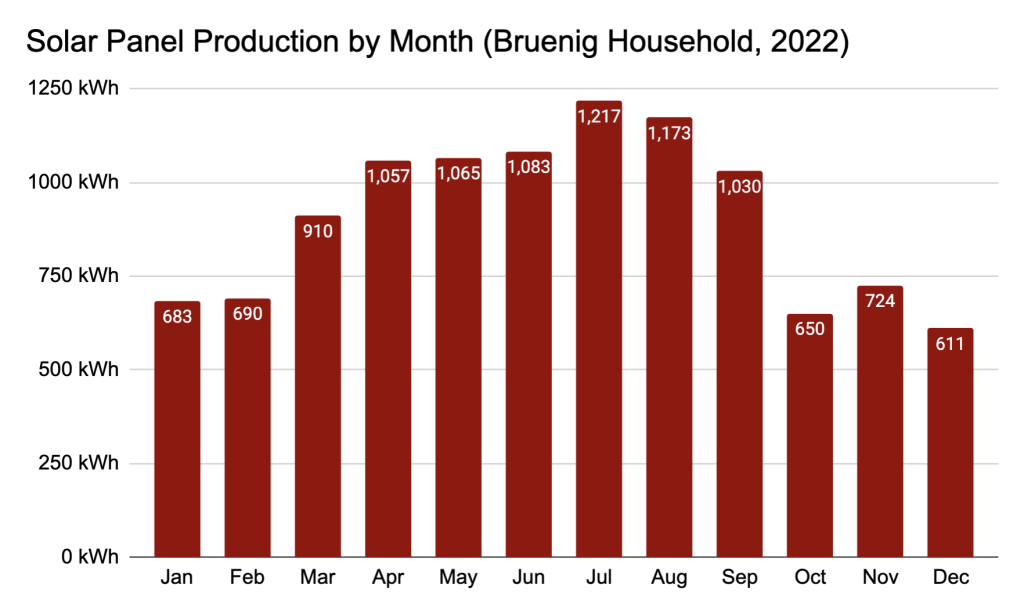

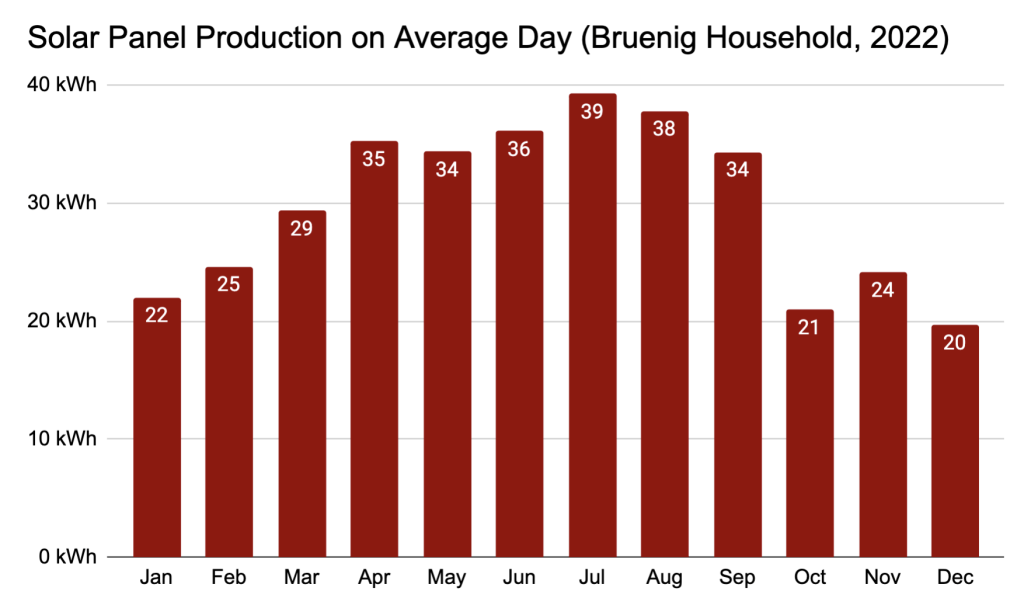

Overall, in 2022, the solar panels produced 10,894 kWh of electricity. This is consistent with the estimate the solar company provided that said the system would produce 193,545 kWh over 20 years.

The amount of electricity produced by the panels varied across the year in the predictable pattern: sunny summer months produced more electricity while dark winter months produced less electricity.

Financial Assessment

To asses the financial impact of the solar panels, I need to compare how much it cost to buy the panels to how much the panels reduce my electric bills.

The unsubsidized all-in price for buying and installing the panels was $25,525.43. In the year that I bought the system, I was eligible for a federal tax credit equal to 26 percent of this price (this credit has recently been increased to 30 percent). So, after counting this $6,636.61 tax credit, the subsidized price was $18,888.82.

The solar loan I was offered to cover the purchase was a 20-year loan with a fixed 4.99% interest rate. The lender would allow you to take out the loan for the full unsubsidized price of the panels (the $25.5k amount) or for the subsidized price of the panels (the $18.9k amount). If you took out a loan based on the unsubsidized price, then you get to receive the $6.6k federal tax credit as a cash refund at tax time, but your monthly loan payments would be higher ($174.39 per month). If you took out a loan based on the subsidized price, then you had to hand over the $6.6k federal tax credit to the solar lender in exchange for lower monthly payments ($128.54 per month).

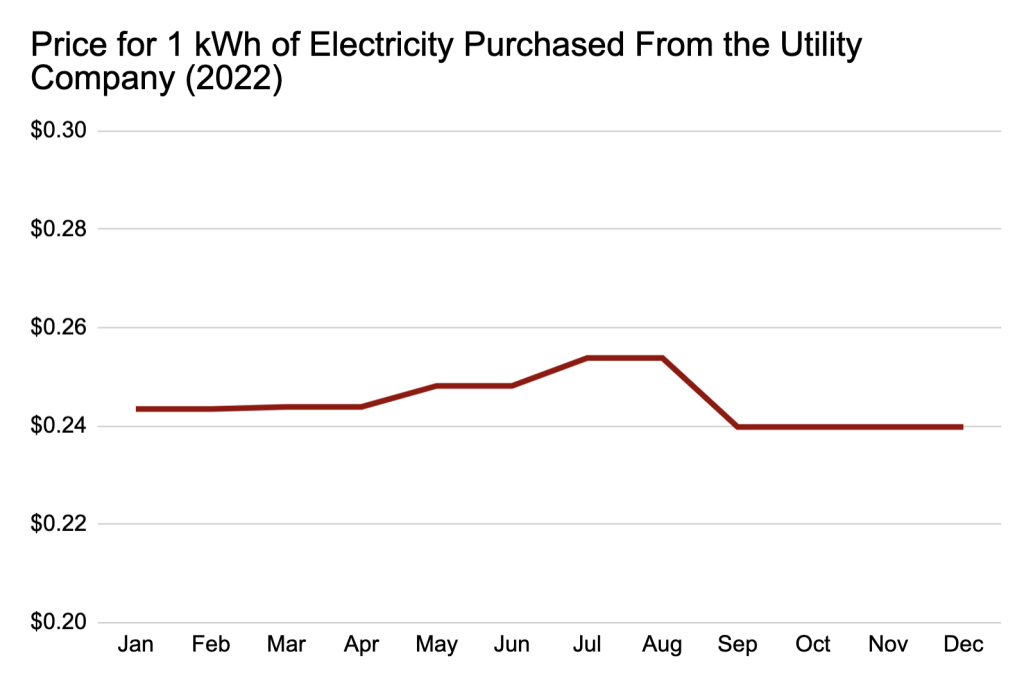

To calculate how much I saved on my electric bill during the year, I need to multiply my electricity production by the price of electricity being charged by the utility company. In my case, the per-kWh price of electricity was around 25 cents for the year, with the exact price varying month to month due to price changes approved by the utility regulator.

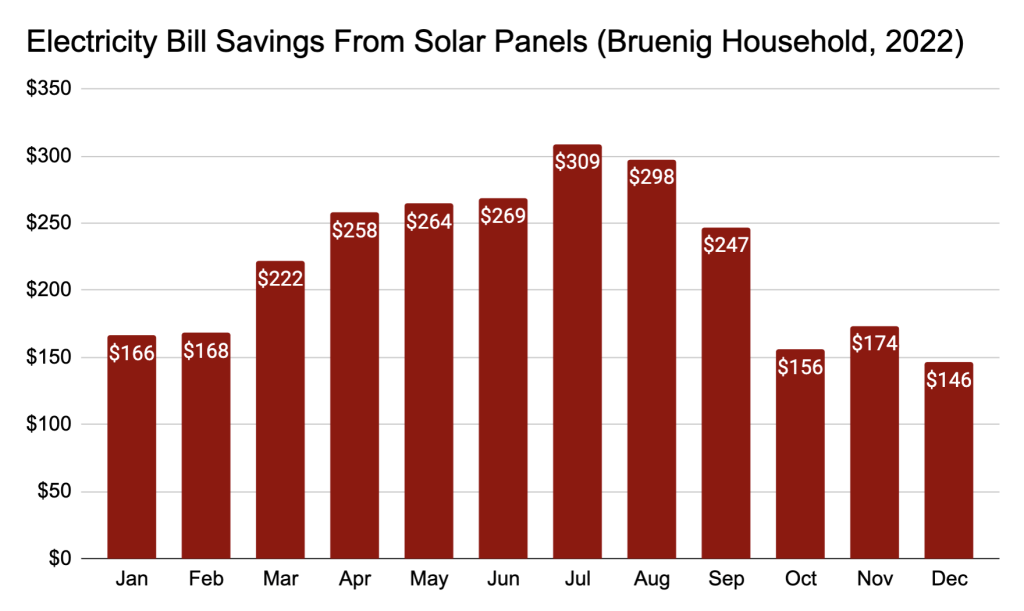

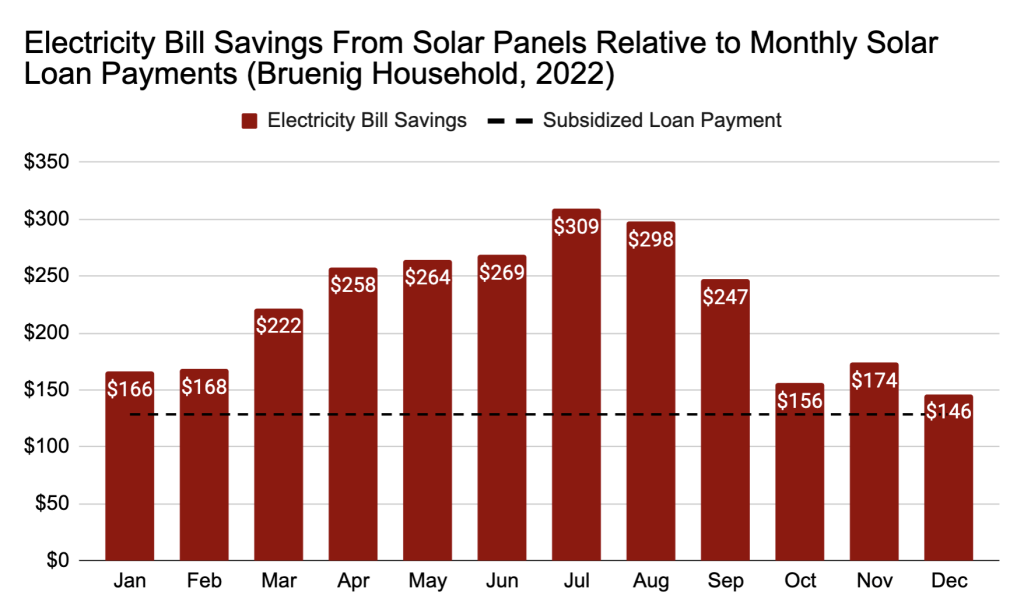

If we multiply the monthly per-kWh price of electricity by the monthly output of my solar system, then we get the following graph of monthly savings.

On an average month, the solar system saved me $215 on my electric bill. To get an initial sense of how much net savings this resulted in, below is the same graph but with a line drawn at $128.54 that reflects the monthly payment required by the solar loan if taken out at the subsidized price. As you can see, the savings exceed the loan repayment amount in all 12 months, meaning that if you used a loan to finance your panels in this way, you would be cashflow positive immediately.

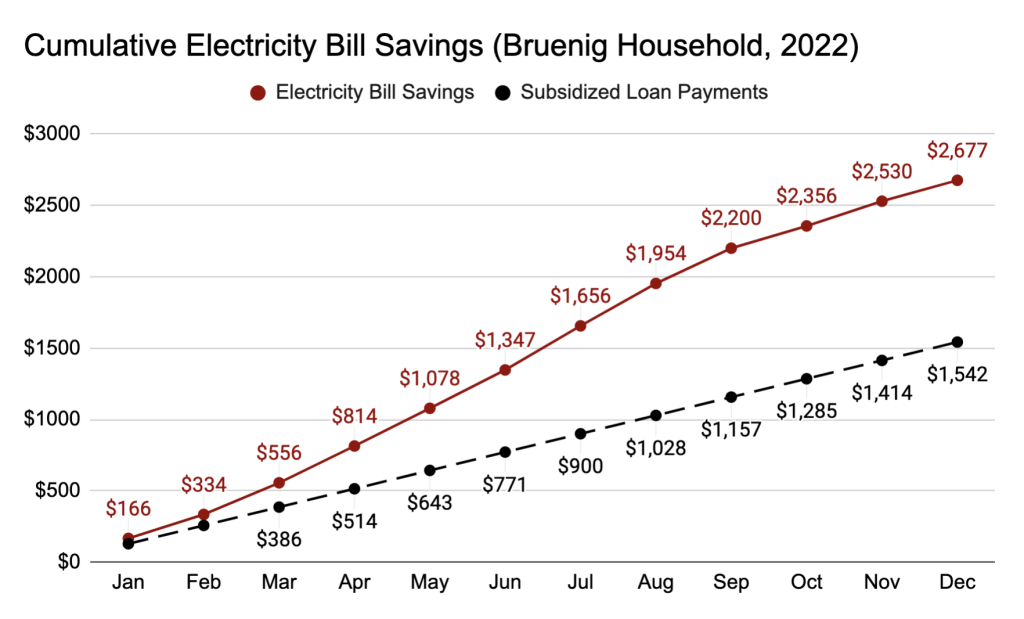

In the next graph, I have displayed this same data, but as a cumulative figure. Across all of 2022, my cumulative electric bill savings were $2,677. Had I used the solar loan at the subsidized price to finance the panels, my cumulative loan payments would have been $1,542.

For people who pay for their solar panels in cash, the typical approach to doing a financial assessment of them is to calculate how long it takes for them to make back the money they spent on the panels. Remember from above, the subsidized price of the panels was just under $18.9k while the annual savings on the electric bill was $2,677. If every year results in this kind of savings, then the panels will pay themselves back in 7 years. The remaining 13 years on the “lifetime” of the panels would thus be profit.

But this estimate probably understates things a bit. The $2,677 savings was based on the price of electricity in 2022. Yet prices generally increase some year to year. In my case, the price of electricity is going up by a little over 30 percent on January 1, 2023 due to the rising cost of natural gas. If these prices hold for the entire year, then my savings next year will be $3,480 and the amount of time it takes for the panels to pay for themselves will go down.

This kind of years-to-payback math makes sense for what most people care about when thinking about personal finance. But there are some slightly more sophisticated ways to approach this kind of financial assessment.

If we take the $18.9k subsidized price of the panels and do a straight-line 20-year depreciation of it, we get an annual depreciation of $944. Under this accounting approach, I am effectively spending $944 per year and am receiving a benefit equal to the amount I save on my electricity bill, which, in 2022, was $2,677. This means that every dollar I spend on the solar panels returns $2.8 dollars of electric bill savings. Turning $1 into $2.8 dollars is a huge return that exceeds almost any other investment you will ever find, especially once you adjust for the riskiness of alternative investments.

Another approach is to find the net present value of the future flow of electricity bill savings and then compare it to the subsidized price of the panels. In this case, if you use a 5 percent discount rate, 20 years of $2,677 of annual electricity bill savings yields a net present value of $33,361. This is $14,472 more than the initial investment. And as noted already above, the future electricity bill savings are probably going to exceed $2,677 per year, meaning that this is an understatement.

Lastly, if you use a loan, the math is a lot simpler. In the 4.99% interest rate loan above, we see that, in a given year, we spend $1,542 on the principal and interest payments for the loan while saving $2,677 on the electric bill. This shows that even after giving out a 4.99% return to the bank, we are still turning $1 into $1.7, which is a massive return that will exceed any other alternative investment, especially on a risk-adjusted basis.

In my own case, the financing arrangement ended up being quite unusual, which is why, so far, I have focused on what the financial assessment would have been if things had played out the way they usually do with either a cash purchase or solar loan.

When I initially contracted for the panels, I agreed to the solar loan discussed above. But the terms of that loan required that the panels be installed within 6 months or else my loan approval would lapse. Due to widely-reported problems with the solar market around that time, the solar company ended up installing the panels 7 months after I signed the contract. When they went to the bank to get their money and start the loan, the bank informed them that the contract had expired and they could not release the money.

This resulted in a rather hilarious situation in which I had fully-functioning solar panels on my house but no underlying contract to purchase or finance them as the contract had expired. Solar companies and lenders certainly have a process for dealing with people who default on their payment, including repossession of the panels, but my non-payment would not be a default because default is defined by a breach of contract and no such contract existed. Indeed, if anyone breached the contract, it was the solar company by not installing in the six-month period.

Realizing that the solar company was in quite the pickle insofar as repossessing the panels would require costly legal actions on top of paying people to take out the system, I just waited on the payment. They would contact me periodically asking me to make payment and offering to help me get approved for a new loan. But I just ignored all of that.

After about 9 months, they began to send me harsher letters, including hand-delivered letters that sort of looked like process-serving. This was all meant to make it look like they were turning up the heat and things were going to come crashing down. At one point they even said someone would be sent out to turn the system off on a certain date. But I knew that this could not be done without first going through a court, which they had not done, and so I ignored this threat as well. As expected, they did not follow through with this threat.

After all of this, including a few phone calls with higher-level collections staffers at the company, they seemed to eventually realize that I knew the pickle they were in and so they softened their negotiating stance. They had breached the contract, not me. The loan terms available to me in late 2022 were less favorable than the loan terms available to me in the middle of 2021. They could go through the legal process to get an order allowing them to repossess the panels, but this would be costly. In short, I made it clear that they needed to bring the price down if they wanted to see any money from all of this.

I told them that I would be willing to settle this issue in exchange for a $5,525 discount, which brought the unsubsidized price of the panels down from $25.5k to $20k. They agreed and so the final price I paid for the panels, net of the federal subsidy, this discount, and 2% cash back on my credit card purchase, was $12,963. Needless to say, the return on this investment far exceeds even the very high returns already discussed above.

There is another variable that you will need to take into consideration in order to make a financial assessment in your situation, which is how your area handles net metering. During the day, solar panels typically produce more electricity than you consume. During the night, they don’t produce any electricity and so you need some other source of electricity.

If your area does not allow net metering, then the only way to make use of all your electricity is to buy a big and expensive battery that stores electricity during the day so you can use it at night.

If your area allows net metering, then you can send your surplus energy during the day onto the grid and get a credit that allows you to offset the energy you consume from the grid in the evening. In some areas, if you send more overall electricity to the grid than you consume from the grid, they will even pay for the difference. In other areas, you can use your credits to entirely offset what you consume from the grid, but they will not pay you for any credits beyond that.

Broader Considerations

The above walks you through the personal finance considerations behind getting solar panels installed on your home’s rooftop. In general, it appears to be a wise financial decision.

But solar panels are more frequently discussed in the context of climate change. These discussions generate fierce debate about how viable solar panels really are as a replacement for carbon-based energy sources and somewhat less fierce debate about whether residential rooftop solar is a good use of scarce solar resources.

The argument that solar panels are not a good replacement for carbon-based energy is centered on the fact that solar energy is intermittent and the fact that, right now, storing solar energy is difficult and costly to do, especially at the scales that would be needed to deal with intermittency.

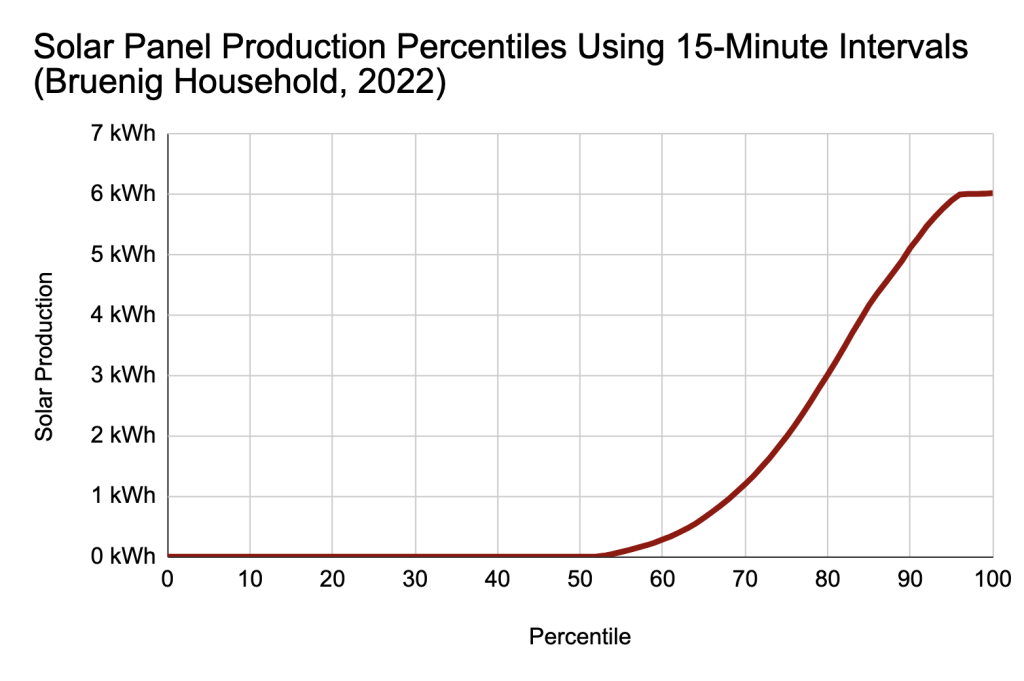

From my own panels, it’s clear enough that production is very intermittent. In the below graph, I take all 15-minute intervals of production from the last year and sort them from most productive to least productive and then graph production levels by percentile.

Most of the time, the panels produced no energy. The panels produced at their maximum potential only around 5 percent of the time. The remaining 40 percent of the time, the production was quite varied. Given this intermittency, certainly the critics are right that solar power cannot scale to provide all of the energy we need. But, to my mind, the upshot of this argument is that we should only install as much solar as we can practically use given its current limitations and that we should try to innovate to lessen its limitations, not that we shouldn’t install solar at all. We have not yet reached the limit of what can practically be achieved with solar power and so solar installations should continue for the time being.

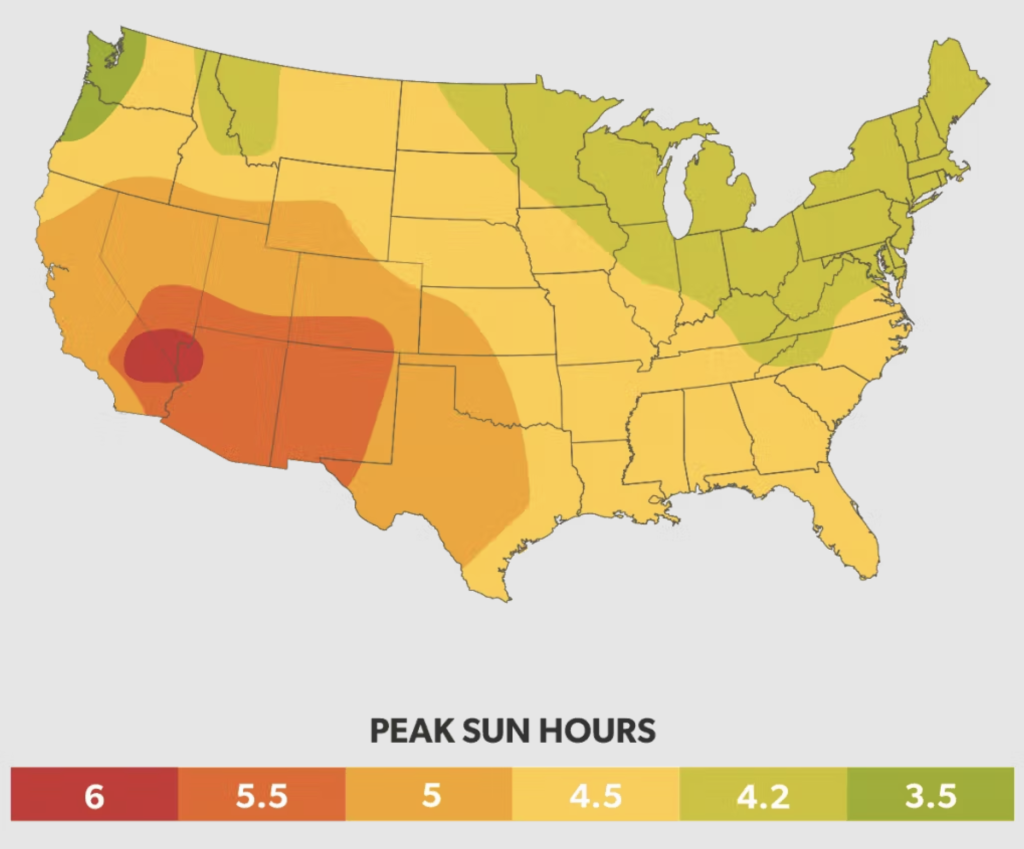

The argument that rooftop solar is not an efficient use of scarce solar resources is centered on the fact that residential solar installations are twice as costly as utility-scale solar installations on a per-kWh basis. Also, residential solar panels are being installed all across the country rather than being concentrated in the areas with the most annual sun hours.

I find this argument fairly persuasive. As solar panels roll off the assembly lines, it seems like they should be allocated to wherever they can produce the most usable energy at the lowest cost. For the US, that means prioritizing utility-scale solar installations in the southwest of the country. My residential-scale solar installation in New England is one of the worst places to locate scarce solar production resources and it probably does not make sense for the government to be subsidizing such installations in the way that it currently is.

But that’s the policy we have and, as individuals, we have to make decisions within the system we have. That system makes rooftop solar a smart personal financial decision for many people and those people should probably take advantage of the opportunity.