I read this piece from Freddie deBoer today about the importance of normie politics, which he defines as:

A politics that plays to the electorate’s sense of normalcy and which assuages their fundamental fear of change through symbol. Normie politics is not inherently moderate but rather presents its positions and candidates as commonsensical and in keeping with folk wisdom.

On the general point, I think Freddie is right. When you are promoting something to the broader public — whether an idea, a candidate, or something similar — it is usually better to do so with words and images that make it seem normal as opposed to radical.

This is one of the reasons why, when I make socialist or social democratic policy proposals, I like to give examples of the policy in question working elsewhere and focus more on the technical aspects of it rather than the ideological valence of it.

In making this general point, Freddie chose an interesting example that he believes supports the point, but which I think may actually cut against it. The example is John Fetterman, which Freddie discusses this way:

You might be forgiven, at first glance, for making some assumptions about John Fetterman. Given his bushy goatee, preference for jeans and work boots, and various tattoos, you might assume Fetterman is a roadie for Metallica, or perhaps a proud restaurant owner appearing on Diners, Drive-ins, & Dives. But Fetterman is in fact the Democratic candidate for Senate in Pennsylvania, a genuine radical in comparison with mainstream American politics, and a frontrunner. And I suspect that it’s precisely his regular-dude vibe that has helped him secure his polling advantage

The problem with the Fetterman example is that his presentational choices are actually quite abnormal for a politician. Virtually all male politicians dress like businessmen. Fetterman dresses like an auto mechanic, which is really strange even though it’s also kind of cool.

Now perhaps Fetterman has figured out a latent preference among voters for politicians who dress like blue-collar guys and soon the rest of the political world will catch up to his innovation. But what’s more likely is that Fetterman’s ability to dress like that and be a successful politician is an anomaly and that most people who tried it would be seen as unserious by voters.

Another way to say this is that normalcy is context-specific and, in the context of being a politician, Fetterman has rejected normalcy and this seems to have played to his advantage rather than hurt him, as it probably would in most cases.

I’ve thought a lot about this sartorial question over the years as I am a lawyer who prefers to dress like John Fetterman. When I worked for labor unions, I thought it might be fine to dress like this and that it may even help me be more relatable to working class clients. After all, they are more familiar with people who dress like that than people who dress like lawyers. And lawyers dress more like management, the enemy of the aggrieved union worker.

But this intuition did not prove to be totally correct. Production-level workers may have considerable antipathy towards the professional-managerial class, but when they need a lawyer, they want a lawyer, a good one that dresses like a lawyer.

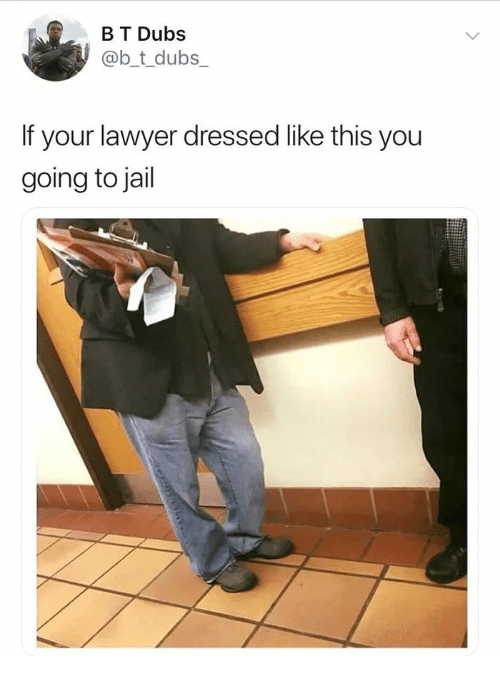

This holds for other kinds of lawyering that interfaces with working class people. Indeed, there is an amusing meme template about how badly-dressed lawyers indicate that you are going to get bad representation, such as below.

I really do not like the fact that our culture expects these kinds of sartorial divergences between different classes and professions and absolutely detest that elected representatives are expected to dress as businessmen. But in the world as it is right now, that is normal, which means Fetterman is behaving very abnormally.

The interesting question is how he has made this unusual presentation work for him.