Terrence McCoy has a long piece in the Washington Post about multi-generational disability. Or, more accurately, a piece about one family McCoy spent a few days with. The only parts of the piece that try to quantify multi-generational disability make very little sense.

Households with multiple family members on disability

From the article:

As the number of working-age Americans receiving disability rose from 7.7 million in 1996 to 13 million in 2015, so did the number of households with multiple family members on disability, climbing from an estimated 525,000 in 2000 to an estimated 850,000 in 2015, according to a Post analysis of census data. The analysis is probably an undercount.

The first problem is that “multiple family members” is not the same thing as “family members from different generations.” Two spouses would count. Two siblings would count. And so on.

The second problem is that you can be “on disability” without being disabled if you have a disabled parent. When a parent is receiving SSDI benefits, each child they have will receive a benefit equal to 50 percent of their parent’s benefit, subject to an overall family benefit limit. Children do not need to be disabled to receive this benefit. They receive it simply because their parent is disabled.

The third problem is that the household counts for 2000 and 2015 should be divided by the number of households in the country to convey the real magnitude of the change. In 2000, there were 104.7 million households, meaning that 0.5 percent of households had multiple family members on disability. In 2015, there were 124.6 million households, meaning that 0.7 percent fell into this category. That’s the crisis, apparently.

Rich disabled kids

The other data element of the piece uses the American Community Survey to determine how often disabled children have a disabled parent. This data does not show how often children and adults in the same household both receive disability benefits, only how often children and adults in the same household tell survey workers that they have one of the five serious disabilities tracked by the Census.

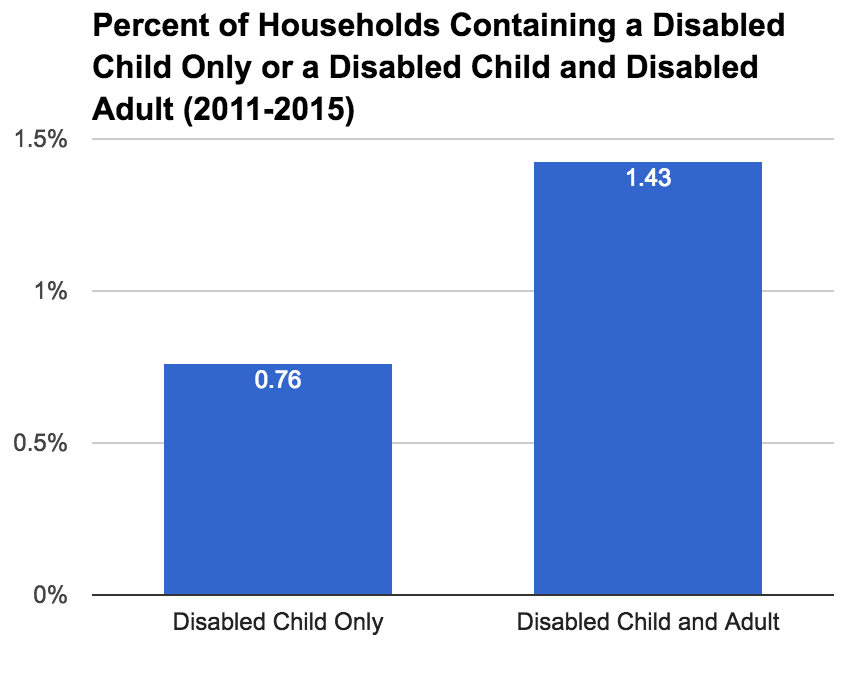

I used the same ACS file to produce a similar calculation as the one made in the piece. For my calculation, I kept things really simple. I isolated two types of households: 1) those with disabled children in them but no disabled adults, and 2) those with disabled children and disabled adults in them. Then I divided the number of households described by (1) and (2) by the total number of households in the file.

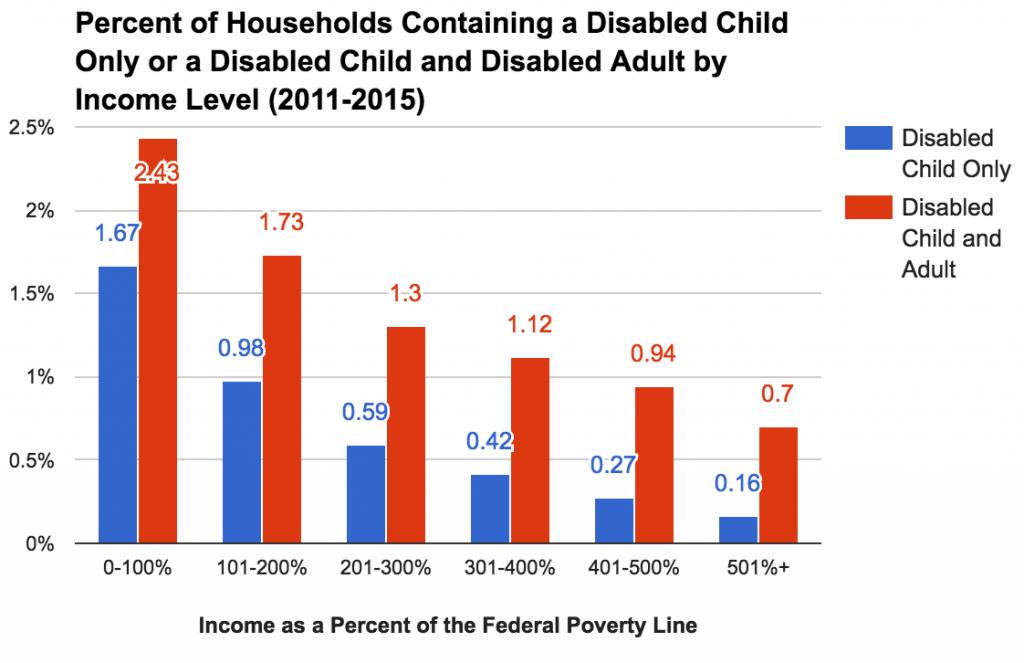

Here is the same calculation but broken up by income level, again in a similar way as the piece in question did:

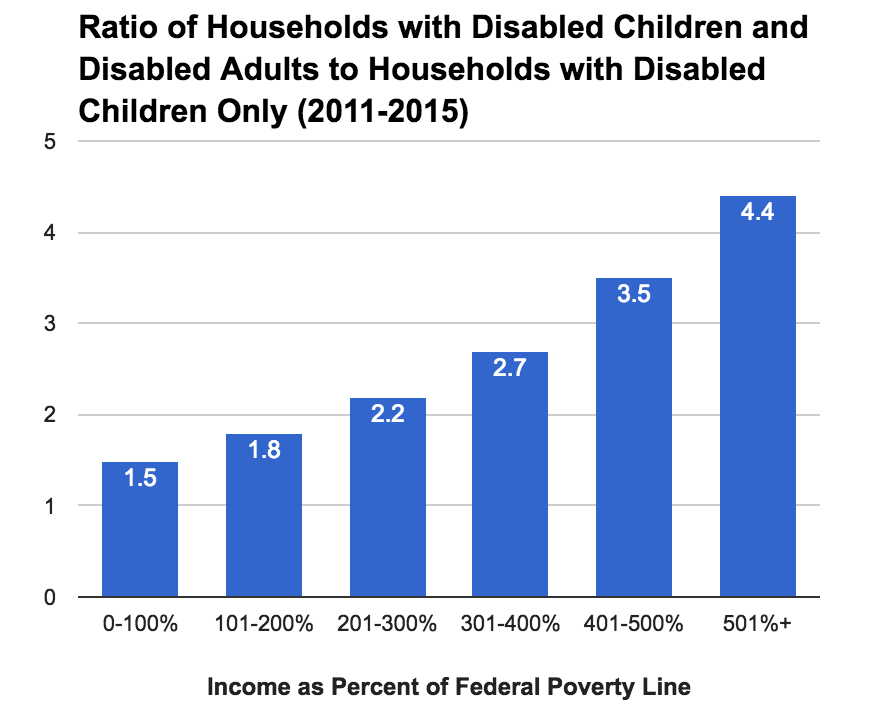

Here is the same graph, but I divide the red bars by the blue bars to get a ratio:

These figures do not substantially differ in their trend from what is presented in the piece, though they are more detailed and use all households for their denominator rather than whatever denominator the piece decided to use.

The data element in the piece is presented without much commentary, but the patterns shown in the above graphs are actually at odds with the welfare cheating story that the piece is trying to tell.

The only disability benefit children can get for being disabled themselves is from the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. That program is means-tested, meaning that only children in lower-income families can receive it. For those with incomes over the quite low limits, claiming your child is disabled is of no use to you as far as welfare income goes. Yet, child disability is related to adult disability up and down the entire income distribution. In fact, the odds of a disabled child also having a disabled parent gets larger as you move up the income scale.

The welfare-cheat model suggested by the piece is supposed to be that you have an adult who is on disability; they then realize that if they claim their kid is disabled, they can get more benefits; so they do that. But this model would predict the opposite of what you see in the last graph. The likelihood that a “disabled” child is in the same household as a disabled adult should go down as you climb the income ladder because there is no way to cheat welfare money when your household income puts you above the SSI eligibility thresholds. Instead, the likelihood goes up and up and up even as the incentives to spoof your kid’s disability go down and down and down.