I’ve been reading the recent EPI report from Elise Gould, Alyssa Davis, and Will Kimball titled “Broad-Based Wage Growth Is A Key Tool In The Fight Against Poverty.” The report shows, as you would expect, that if earners at the bottom had higher market incomes, then poverty would be somewhat lower as well. While there is little to quibble about in this regard, it’s hard to see (even in the report’s own figures) how wage growth alone is meant to get us anywhere near the rock-bottom poverty we should be aiming for.

Most Poor People Are Not Employable (At This Stage in Their Life)

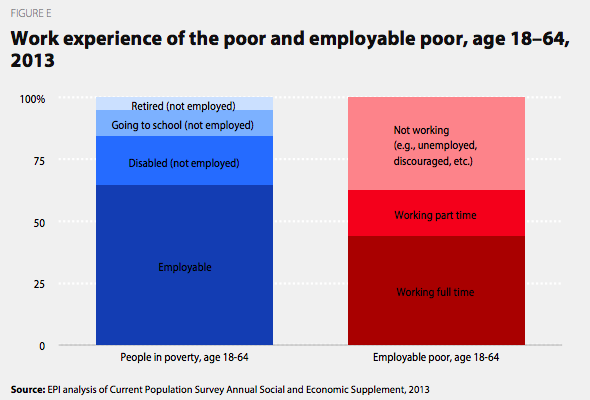

The authors give us this graph which shows that the majority of adults in poverty are employable and the majority of employable poor adults are indeed employed.

It follows then that increased wages and a full employment economy would direct more market income to those who are working, provide more full time work to the poor who work part-time involuntarily, and activate more of the employable poor who are currently not working due to involuntary unemployment, discouragement, or whatnot. Together, this would cut poverty.

This makes perfect sense for what it is, but if you look closely at this graph, you’ll actually see just how small the employable portion of the poor actually are.

By narrowing the focus on people aged 18-64, the graph immediately (and rightly) excludes children and the elderly from the employable. By my calculations, children and the elderly constitute 32.3% and 9.3% of the official poor respectively, or 41.6% combined.

Of the 18-64 adults the graph does include, around 35% are not employable because they are disabled, students, or retired. Personally, I don’t count the retired 18-64 as necessarily unemployable myself. If we bring them back into the theoretically employable bucket, that means we identify as unemployable the disabled (13.9% of all poor) and students (9.8% of all poor). If you add in the elderly and children discussed in the prior paragraph, that brings us to a cumulative total at this point of 65.4% of poor people being unemployable. Which is to say: around 2 in 3 poor people are not in a position to pull down more market income.

But that still leaves the other 1 in 3 poor people, right? Well, yes and no. As I discussed before (I, II), around 19.6% of the officially poor were non-disabled, non-student working adults in 2013. Another 3.7% of the officially poor were non-disabled, non-student adults who were involuntarily unemployed for the entire year. Combined then, around 23.3% of the poor (not 1 in 3) fall in the camp who would clearly be able to benefit from the higher-wage, full employment economy.

In addition to those 23.3% of poor people, there is another 11.1% of the poor who are non-disabled, non-student adults who maybe could be activated into the labor force by higher wages. I say maybe because 7.8 percentage points of those 11.1% are made up of people who say they don’t work because they are taking care of home and family (i.e. they are carers). Perhaps higher wages could entice them out of their care work, but also maybe that really just isn’t possible for them.

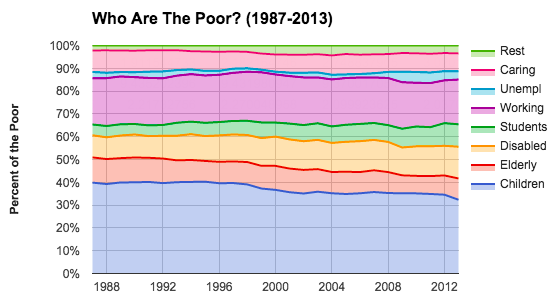

In sum, then, the overall picture of the poor (as is partially painted by the EPI graph) turns out like this:

The super-majority of the poor are unemployable right from the start. The “Working” and “Unemployed” are employable, while the “Caring” and “Rest” are maybes. Of course many of the unemployable poor live in families with the employable poor (especially children) and so through that family income mechanism, many of them would benefit as well from market income boosts. But be that as it may, it’s still the case that the story of poverty is overwhelming the story of those the market, by its core nature, discards as useless. This means market income mechanisms are likely always going to struggle to actually stamp out poverty.

Poverty Rate Still High Under Counterfactuals

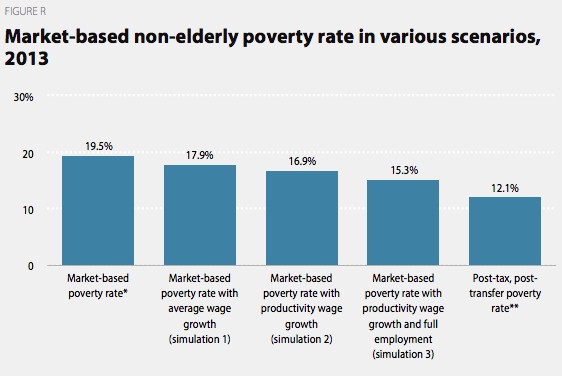

Interestingly, the report itself gives a pretty good indicator of this. Consider this payoff graph that the whole report builds up to:

Even when you ignore the elderly (who have super high market poverty), assume wage growth at the bottom had matched economy-wide productivity growth since 1979, and assume full employment, you still find yourself in a scenario where greater than 1 in 7 people are in market poverty!

I bring this up not to criticize higher wages. Obviously increasing hourly pay is a wonderful thing. I don’t think anybody would argue otherwise. But it’s important to always highlight the limits of market-focused anti-poverty strategies. If you really want to run those poverty levels to as far down as they can realistically go, what you need to be looking to do is increase transfer incomes and other benefits to children, elderly, disabled, and the unemployed. That is where the low-hanging anti-poverty fruit is really found, especially child benefits, which the US currently has relatively little of. Not only do these kinds of transfer incomes strike at the heart of poverty by targeting the vulnerable populations that primarily comprise it, but when done well they can even help to increase the heavily prized market income, especially the child-focused benefits like child care and paid leave that help facilitate greater labor force participation.