Aaron Bady has a piece about free higher education over at Al Jazeera. As regular readers know, I have endorsed free higher education in the past funded by a graduate tax. So, Bady and I are pretty close together. In the fallout from his piece, a Twitter conversation ensued, which has inspired me to sum up some of my of views on this higher education topic. In so doing, know that my bias tends to be towards the bottom quarter. So I generally look at policy issues through that lens.

1. The concern about the price of higher education for students is driven by price spikes hitting the top half of kids.

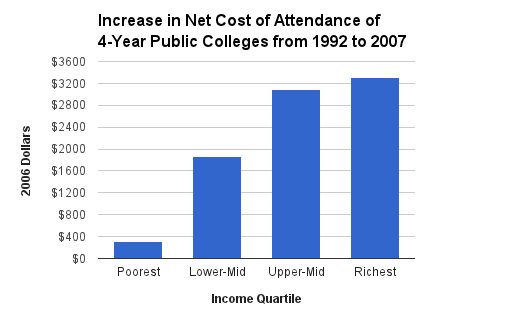

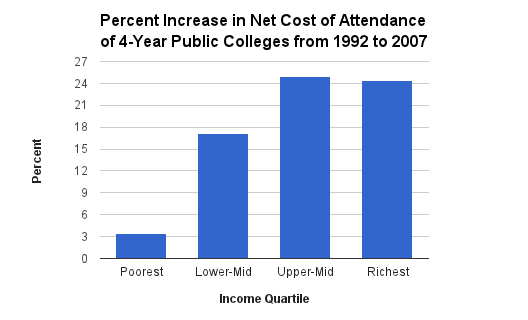

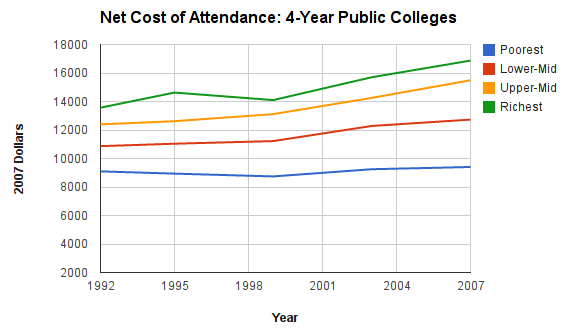

By now the, the refrain is clear. College tuition is soaring. But the reality is actually slightly more complicated. There is not one college tuition. Even at a given institution, students pay different amounts based upon their family income, with poorer students paying less and richer students paying more. At four-year public institutions, net tuition and fees for the poorest quarter has actually fallen since 1992, and total cost of attendance for the poorest quarter has inched up only very slightly. It is everyone else, the upper half especially, that has experienced the spike.

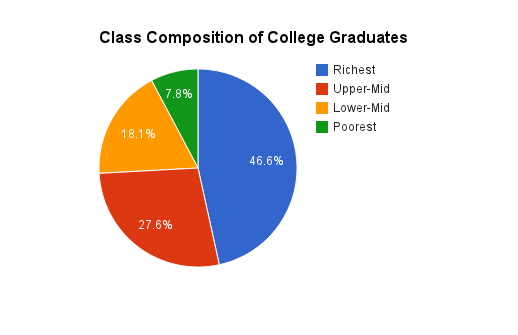

My point here is not just about what students from given backgrounds pay. It is also about the composition of the student body at four year colleges. The Bailey-Dynarski calculations from the latest National Longitudinal Survey of Youth show that four-year college is very much a rich kids’ game. So in addition to paying considerably more and seeing their cost of attendance spike way more over time, richer kids also just make up a hugely disproportionate share the student body of four-year colleges (NLSY does not break out private/public distinction, but most recent NPSAS data show them to be fairly similar).

I speculate that, given who has actually absorbed tuition increases and given the class composition of four-year colleges, the recent grumblings about tuition is driven by the concerns of the richest half. I therefore also speculate that when people argue that they really don’t like the direction of public education tuition because of the effect it is having on the poor, they are not serious. Although they may be genuine in their concern for the poor, I think they decided they didn’t like tuition increases first and then reasoned after the fact and incorrectly that it must be something that is primarily weighing down the least among us. As that flatters the political priors of certain folks, that became a very dominant line of argument.

2. The concern about the the price of higher education for students is about four-year colleges.

Basically every statistic I see about debt, per-pupil subsidies, institutional costs, and so on is actually just about four-year colleges and their students. On a good day, some sparse lip service is paid to community colleges (e.g. Bady’s single mention of them along side his forty mentions of universities), but really four-year colleges is where the show is.

I say this not just based on my impression from regularly reading the people who comment on this. It is also that price hikes have not affected two-year colleges the same way they have affected four-year colleges. In fact, average net tuition and fees for two-year colleges has fallen by over $1100 since 2003. Average cost of attendance has fallen by just over $800. There may be other new and developing problems with community colleges, but with average prices falling, the narrative cannot be the one that is trotted out as representative of higher education as a whole (but is really just about four-year colleges).

This thesis, if true, bolsters the first thesis as well because of the class differences in who attends community colleges and who attends universities.

3. Making four-year colleges free will overwhelmingly benefit rich kids.

As we saw in thesis one, rich kids and the upper half in general are dramatically over-represented in the nation’s four-year universities. We need a theory to explain why this is the case. Some proponents of making four-year colleges free seem to assume that cost is the limiting factor, and that therefore if we made college free, poor kids will become more evenly represented.

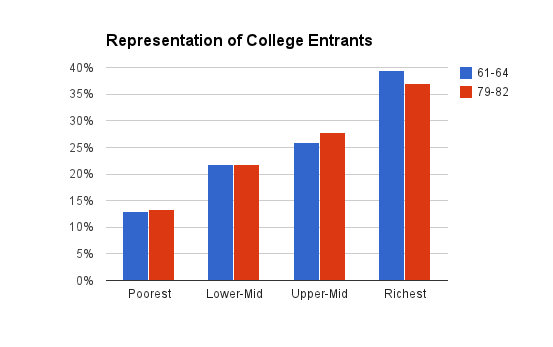

In making this case, they often point to the past when college was much more affordable. But in doing so, they don’t actually produce figures on what the class composition of four-year colleges was in that more affordable past. They appear to just assume that because tuition was lower in the past, things were more accessible.

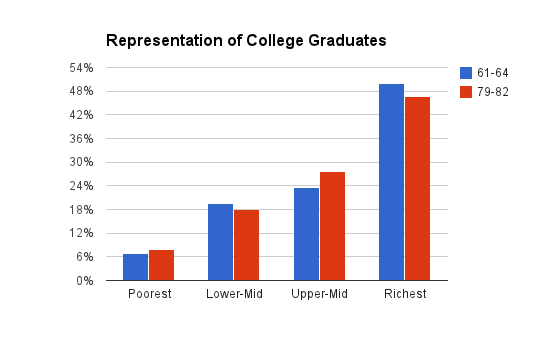

But we do have figures. Again, we turn to Bailey-Dynarski. The share of all four-year college entrants who came from each class and the share of all four-year college graduates who came from each class is largely unchanged since the late 1970s. (In these graphs, the numbers in the legend are birth years for the cohort. So add 18-22 years for when they are hitting college age. Again, NLYS does not break out public/private distinction, but latest NPSAS data show substantial similarity)

I infer from this that the price of college is probably not the dominant factor in determining the class composition of college. In fact, the class composition of college is somewhat more diverse than it used to be in the Golden Era of College Accessibility, as I’ve come to call it.

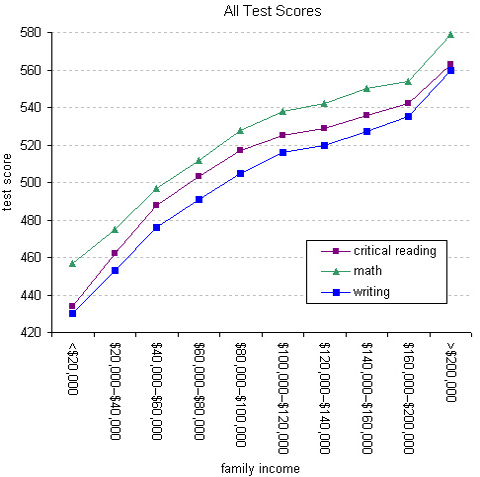

So if that theory does not explain why college is so skewed towards the rich, what does? My operating theory is that poorer people, on account of being poor, have much rougher lives. They are subject to much greater stress (see Poverty Is Poison), have worse nutrition, move around a lot, do not have access to the same kinds of enrichment, and so on. As a result, poor kids are, on the whole, way behind their rich peers. This is illustrated well by this SAT chart broken down by income.

Lowering the price of college to $0 will not change that graph and will not have any effect on the kinds of things that put poor kids way behind their rich peers. As a result, richer kids will still capture most of the four-year college seats (it is, after all, a competition given selective admissions) and the class composition of college will not change.

If the class composition of college will not change in response to college being free (which I think historical and contemporary evidence suggests is the case), then making college free will primarily be a windfall for the disproportionately rich kids who will still be the ones in these college spots.

Making four-year college free would actually be more class lopsided than even the class composition of college suggests. In the status quo, these colleges are disproportionately composed of richer kids, but also richer kids pay way more than poorer kids to attend them. So for instance, according to the Bailey-Dynarski numbers above, there are roughly 6 rich kid college graduates for every 1 poor kid college graduate. But it is also the case, that rich kids at public four-years pay a price that is about 1.8x higher than poor kids at such schools.

So if we assume the class composition of college will remain basically the same (and I think I have some decent reasons for believing that’s the case), subsidizing the cost of attendance of four-year colleges would roughly direct (using this admittedly back of the envelope math) $10.80 to rich kids as a class for every $1 it directs to poor kids as a class, relative to the status quo. This is very rough as these numbers span different years, different college types, and use the college graduate class ratio not college entrant ratio (which is also largely unchanged since the late 70s, but slightly less lopsided at 2.8:1 versus 6:1). The number is somewhere in between as someone who enters college but doesn’t graduate likely uses less of it than someone that does both. I bring the number up here just to make my basic point about just what kind of class lopsided change we would be talking about.