Let’s say I am arguing with a right-winger about implementing a universal basic income (“UBI”). They say to me “I oppose it because 1) it wont actually make the lives of the poor better and 2) I think private charity is the correct institution for this kind of thing.” The right-winger’s reasoning is clear, but what’s not clear is how each reason he provides actually factors into his calculation.

The right-winger might think each reason is sufficient by itself to reach the conclusion that the UBI must be opposed. In this case, to defeat the right-winger, you have to knock out both reasons to win the debate. Knocking out one wont do.

Alternatively, the right-winger might think that the two reasons must exist simultaneously to reach the conclusion that the UBI must be opposed. In this case, to defeat the right-winger, you only have to knock out one of the reasons to win the debate, and it does not matter which one.

Finally, the right-winger might actually think that one of the provided reasons turns the whole debate and that the other one is just sort of a cherry on top if you will. In this case, to defeat the right-winger, you have to knock out the specific reason they think actually turns the whole debate. The cherry-on-top reason is not really relevant to the disposition of the debate.

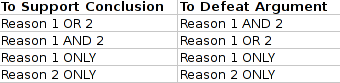

Here is a helpful table that summarizes the above points. In the left column is what the right-winger might think is sufficient to support their conclusion. And in the right column is what arguments I need to knock out to defeat him.

So to proceed in the argument, I have to actually figure out what the right-winger is saying. When he gives this list of two reasons, what does he actually mean? On what row does his argument actually fall?

Stipulations to the Rescue

To tease out what the right-winger is actually arguing, I can stipulate certain facts and ask him how it affects his position. For instance, I can say to him “stipulate for the sake of argument that the UBI will actually make the lives of the poor better, what does that do to your argument?”

The right-winger has three possible ways to respond. He can say “LOL stipulate that, haha, what a joke” and slap his knee and otherwise act like an idiot. In that case you either have to assume he is stupid or can’t argue. Other than that, he can say 1) it changes my position and now I support it, or 2) it does not change my position.

If he says that stipulation changes his position, then that means his original argument was either of the “Reason 1 AND Reason 2” or “Reason 1 ONLY” variety in the chart above. More importantly, it is clearly the case that his whole position will turn on empirical facts that we should be able to establish. If he changes his mind when we stipulate that UBI will help the poor, then he has to argue that it wont do so. That is critical to his position.

If he says that the stipulation does not change his position, then that means the original argument was either of the “Reason 1 OR Reason 2” or “Reason 2 ONLY” variety in the chart above. If this is his position, then he needs to have an argument that says even if the UBI will help the poor, it should be opposed. If he does not have such an argument, then he lied when he said the stipulation doesn’t change his position.

From here, you should be able to see how we could replicate this process, but this time by stipulating that the UBI will come from private charity. His answers to that will actually narrow down his exact argument in the debate (of the four rows in the above chart).

You see how awesome stipulations are? You see how this basic tool of argumentation allows us to drill down to the essence of an argumentative position? It’s great fun.

Now let’s change the example. Instead of a debate about a UBI, let’s assume we are having a debate about MOOCs. The opponent of the MOOC says “I oppose them because 1) they don’t help students, 2) tons of other reasons.” Oh no, we are in the same position as above! We need to use stipulations to start distilling out the actual argument.

Here the stipulation is simple. We can say “stipulate that MOOCs will help students, does that change your position?” If the answer is yes, then the debate critically turns on the student effects of MOOCs, and that’s where the real action is going to be. Studies need to be generated to figure out this empirical question.

If the answer is no, then the MOOC opponent has to be able to present an argument that says even if MOOCs help students, they should be opposed. There are other reasons they are bad that are so compelling that they outweigh positive student effects. That’s a fine position, but you have to actually make it. If you can’t make it, then your position actually does turn on student effects, and you need to go back into the paragraph directly above this.

As it is, most of the MOOC opponents I know just choose the third way of responding to this basic argument clarification strategy, which is to say “LOL stipulate that, haha, what a joke” and slap his knee and otherwise act like an idiot. In so doing, they convince nobody but their in-group, and actually make a strong case for at least replacing them in particular with a MOOC.