Food deserts are areas that have no nearby access to healthy foods. For a period, there seemed to be a furor about food deserts, but that has died down recently. A variety of studies came out challenging the idea that bringing healthy food options into food deserts would have any impact on the consumption of healthy food, and even the idea that food deserts are a widespread phenomenon (I, II, III). When I was still writing about food deserts, my take was pretty standard: food deserts and any health problems they generate are really a derivative problem of low incomes, something building a few supermarkets wont solve.

While poking through the Current Population Survey’s yearly food security supplement, I found some questions that I thought might help us get a grip on how big a problem food access really is. Sadly, the specific questions that I thought most relevant stopped being asked in 2001. So that is the year that the microdata I used for this post comes from.

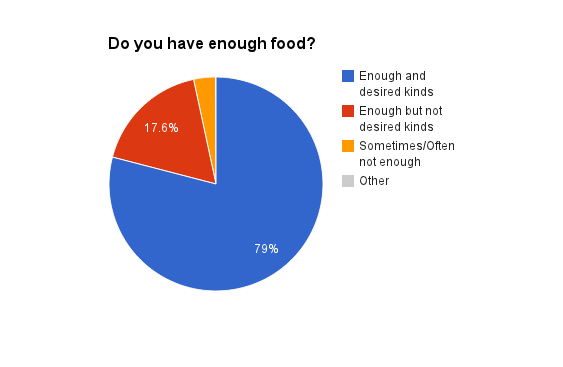

The first thing to establish is how many people are having problems getting the food they need. The Census asked people if, over the last 12 months, they had enough of the kinds of food they wanted to eat. The answers were as follows: 79% said that they had enough food and the kinds of food they wanted to eat, 17.6% said they had enough food but not the kinds they wanted to eat, 3.3% said they sometimes or often did not have enough food, and a very negligible percentage did not answer.

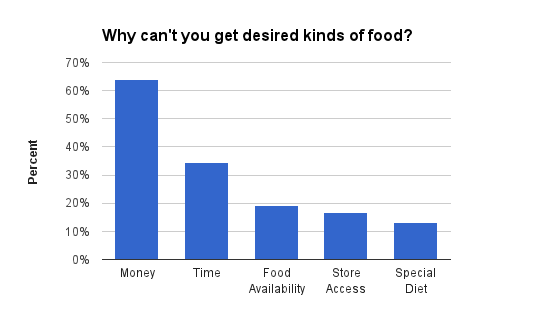

So 20.9% of people answered that they either were not getting enough food or not their desired kinds of food. The obvious next question is: why do they have these food problems? For those who said they had enough food but not the desired kinds of food, the CPS supplement allowed interviewees to select one or more of the following five reasons: 1) not enough money, 2) not enough time for shopping/cooking, 3) the kind of food they want is not available, 4) too hard to get to store, and 5) special diet. The breakdown of those answers looked like this:

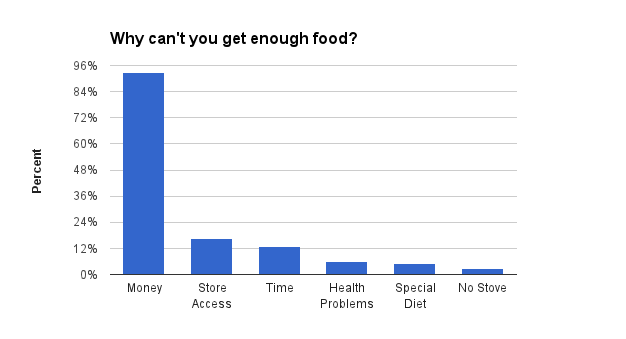

For those who said they often or sometimes did not have enough food, the CPS supplement allowed them to choose among six reasons: 1) not enough money, 2) too hard to get to store, 3) not enough time for shopping/cooking, 4) health problems preventing them from cooking/eating, 5) special diet, and 6) no working stove. The breakdown of those answers looked like this:

Right off the bat, the big takeaway here should be obvious: money dominates any other reason for these food problems. Around 64% of those who had enough food but not the right kinds said this was because of lack of money, and around 93% of those who sometimes or often do not have enough food said this was because of a lack of money. Beyond the money issue, many also cite causes that do not seem to have much to do with geographic proximity to supermarkets or similar sorts of food establishments. Special diets, health problems, lack of a stove, and not enough time to cook will not be solved by plopping a supermarket nearby. The only answers that are directly relevant to the main thesis of the food desert theory are 1) too hard to get to the store, and 2) lack of food availability.

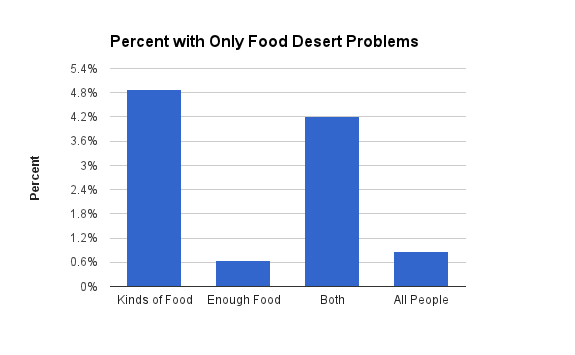

The latter problem — lack of food availability — is not even necessarily a food desert issue. You could imagine someone who had plenty of healthy food around them, but wanted to eat a particular kind of cuisine that was not near them. But bracketing that issue for the moment, let’s assume that the food availability and store access problems could all be solved by plopping supermarkets nearby. What percentage of those with food problems would that actually help? To answer that question, we just need to see what percent of those who did not have enough food or not the desired kind of food only gave store access and/or food availability as the reasons why. Here is what that looks like:

Of those who said they had enough food but not the desired kinds, around 4.9% of them gave only food availability or store access (or both) as the reasons why they can’t get their desired food. Of those who said they cannot get enough food, just 0.6% gave only one or both of those reasons. If we combine those two groups together — people who either could not get enough food or the desired kind of food — the number is 4.2%. Finally, if you put the number of people falling into this camp over all people, it is around 0.9%, which is to say that only 0.9% of people have food problems that increasing their supermarket access alone could solve. And recall, that is when using generous assumptions.

So the point here is that the CPS data does not support the idea that bringing supermarkets into food deserts — if such things even exist in large number — would be sufficient to solve very many food problems. Only a small fraction of those who say they don’t have enough food or the desired kinds of food provide reasons for those problems that greater proximity to food alone could solve. Money is the biggest problem, and has the potential of solving most of the other problems as well. After all, if a community has more money to spend on food and wants to do so, food vendors should move in. Once again, it seems that Give Poor People Money for America is the program to look to for a solution to this problem.