By now, regular readers — and believe it or not there are some — have been treated to my occasional swipes at theories of procedural justice. Roughly speaking, proponents of procedural justice locate justice in the processes that an economy follows. As I have never seen a theory of procedural justice that was not impossible or self-contradicting, I tend to favor distributive justice approaches. Proponents of distributive justice primarily locate justice in the economic distribution of primary goods, capabilities, burdens, and benefits.

As much as that one sentence makes sense to me, I am sure it is much less clear to those who do not know the wonders of Rawls, Sen, Cohen, Dworkin, and the others. The distributive justice literature is rich and goes in many different and complicated directions. What follows is how I would introduce the basics of that body of theory to someone unfamiliar with it.

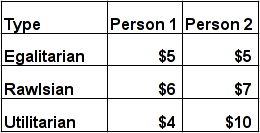

Suppose we had a hypothetical society that consists only of two people. We can construct the institutions of this society in any number of ways, and the way we do so will impact how productive the society is overall and what share of the social product each person receives. With that in mind, how exactly should we construct our society? What should our distributive aim be? Consider the following small selection of distributive possibilities.

The first distributive possibility is simple egalitarianism: everyone gets exactly the same amount. Here I use dollars just to make comparisons easy, but we can replace dollars with burdens, benefits, capabilities, and whatever else. There are good arguments for this distributive aim, and I will explain them below.

The second approach is Rawlsianism. Rawlsianism favors constructing economic institutions according to what John Rawls calls the difference principle. Under such a principle, the aim of economic structures ought to be to maximize the minimum everyone has. Under such a principle, we are permitted to introduce unequal distributions, so long as doing so increases incomes for everyone. Although the step from egalitarianism to Rawlsianism made the two persons unequal, both are better off than they would otherwise be.

The final approach is utilitarianism. It is utilitarian because $4 + $10 is $14, and that amount is higher than the sum of any other distribution. So — ignoring heterogeneous utility functions and the diminishing marginal utility of money — the utilitarian possibility delivers the most overall enjoyment in society, even if it is distributed the most unequally.

In considering the arguments for the different distributive approaches, it is best to start with Rawlsianism. The Rawlsian argument starts with this question: assuming you did not know in advance which person you would be, which distribution would you choose? Rawls argues that you would choose the distribution which maximizes the minimum amount of the worse off person. You would not want to do with less money than you have to or risk being on the losing end of any other distributive choice. So in this case, the Rawlsian distribution is the best one because it distributes $6 to Person 1, which is more than Person 1 gets in any other option.

Defenders of egalitarianism have at least two arguments against the Rawlsian approach. First, some argue that the introduction of inequality in and of itself creates social problems. This is the basic thesis of The Spirit Level. At some point, marginal increases in total consumption do not deliver that much more enjoyment or happiness. Meanwhile, the inequality required for those marginal increases creates problems that outweigh the marginal enjoyment that results from the increased production. Thus, in sufficiently wealthy societies, the Rawlsian difference principle falls down: persons really would choose more equality even if it meant less overall consumption for everybody.

This egalitarian critique does not bring us to the distribution above though. Instead, it simply says that there are limits to how far Rawlsian reasoning can go: even consumption-boosting introductions of inequality would be opposed in some situations because of the social problems such inequality generates. Although there are few people who would actually argue for the egalitarian choice over the Rawlsian choice as laid out in the table, there are those who say the choice is a false one.

G.A. Cohen famously argued that unequal distributions are never necessary to increase the position of the least advantaged. The Rawlsian position assumes that in some instances, people will not undertake additional work unless they can receive more than an equal share of the spoils of that work. So imagine that we are at the egalitarian distribution where both persons have $5. Person 2 is willing to produce $3 more worth of stuff, but only if he can keep 2/3rds of that stuff instead of the usual 1/2. That is, he will only undergo that work with the extra incentive.

Rawlsians argue that under such a situation, we should allow Person 2 to take more than his equal share to get him to do the extra work. If allowing him to keep 2/3rds of the extra production does indeed move him to work, then Person 1 will be better off because he will get the remainder of that extra production. Cohen objects that the necessity of inequality here is only a feature of Person 2’s demands. If Person 2 would behave fairly and morally, he would undergo the extra work without demanding more than his equal share. So, according to Cohen’s argument, the Rawlsian choice is a false one. The choice is not between a $5-$5 distribution and a $6-$7 distribution. If people actually participated morally, we could have a $6.5-$6.5 distribution instead.

Underlying this dispute is a human nature quibble of some sort. Rawlsianism takes for granted that disequalizing incentives will sometimes be necessary to spur production, and argues that they are permissible because they can be harnessed so as to improve the lot of everyone. Cohen’s critique says that such incentives are not necessary unless people make them necessary by refusing to behave and participate in a moral egalitarian fashion. If people can be persuaded to act according to a Rawlsian political framework, then why not just persuade them to act according to an egalitarian political framework and actually improve the lot of the worse off even more?