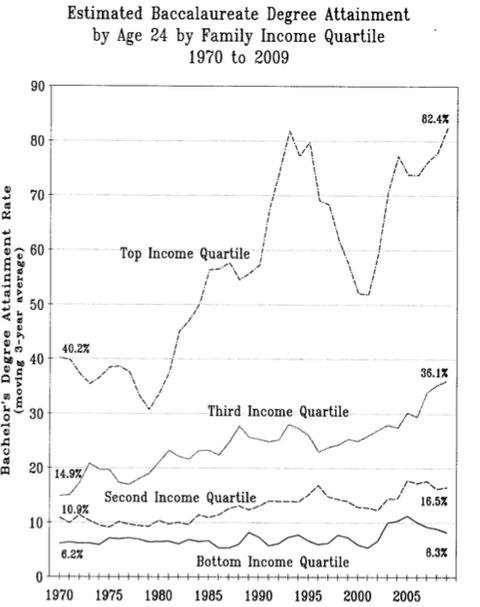

Are there poor kids who attend college against all the odds, take on student debt to finance it, and graduate with terrible job prospects under mountains of debt? The answer of course is yes. But that is not the typical case for students. As I have mentioned before, only 3 percent of students in the expensive tier one institutions come from the bottom quarter of households. Poor kids who do go to college tend to cluster in community colleges which are far less expensive. Consider the following two graphs:

Not surprisingly, higher educational attainment skews quite heavily to wealthier kids. Additionally, take a look at this chart put together by EPI:

This chart is troubling on two fronts. First, it shows once again that college attainment skews towards the well-off. Second, it shows that it skews towards the well-off even when poorer kids are identically-situated in 8th grade math. Wealthier kids tend to score higher already, but even poorer kids who score just as high ultimately fall behind. Many poorer kids are clearly falling behind in high school, putting them out of the reach of college. Even those who manage to maintain scoring parity with well-off kids are less likely to go to college or come out with a degree, for any number of reasons.

My point in all of this is to say that, except for community colleges, student issues really are primarily the issues of the well-off. The real class issues in educational disparity pop up way before college, and will not be remedied by focusing on college. If we are really interested in helping poor kids — not just using a handful of their stories to promote policies that will primarily benefit kids from wealthy households — then we should direct money towards them before they turn 18. Once college rolls around, it is too late for most of them.

Lastly, can we stop describing student debt as burdening a generation? A higher percentage of younger people have student debt now than before, but a super-majority of those under the age of 35 have no student debt, and those with the most student debt are those with the highest incomes.

Referring to student issues, college graduate issues, and educational loan issues as generational issues substitutes the experiences of the relatively affluent for the experiences of the generation as a whole. Using identitarian language, we would say that this characterization is an erasure and marginalization of the experiences of poor youths who by and large are not in college and have no student debt. Ultimately, it is these youths who are in the worst economic position, even as we give their better-off cohorts all the policy and media attention.