Despite the two-year anniversary of the official end of the latest recession, around 14 million people are still unemployed, and the unemployment rate is at a staggering 9.2 percent. With the last couple of months having been monopolized by the high-stakes debt-ceiling theatre, this particular problem has been completely neglected with the exception of a few dogged commentators.

I am worried that as the unemployment crisis lingers on, many will eventually become tired of the problem altogether. Despite the fact that they did not cause the financial crisis, efforts to implicate the unemployed for their plight have already begun seeping into conversations about the issue. Some individuals refuse to believe that the unemployed cannot find a job, and as time progresses that sentiment will no doubt become more widespread. I can already imagine what the rhetorical line will be: “if you haven’t found a job 3-4 years after the recession, you must be lazy.”

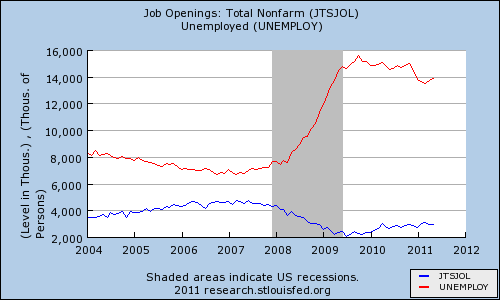

As the above chart indicates, the chances of an unemployed person landing a job still remains dismally low. There are just far too many unemployed persons per job opening. Although it has declined significantly since its peak, the ratio of unemployed persons per open job currently stands at 4.7. Even if every unemployed person was doing absolutely everything they could to fill those jobs, around 79 percent of them would still be out of luck.

With the number of job openings still as low as it is, the unemployed have very few if any places to find employment. Although the total inaction on this problem might seem to indicate otherwise, this level of unemployment is not unavoidable. There are ways that the government could act to decrease unemployment significantly.

For instance, the government could undertake a fiscal stimulus project. Despite the ignorant commentary to the contrary, the first stimulus did help soften the blow of the recession even if it was not big enough to completely turn it around. Allocating hundreds of billions of dollars for infrastructure projects and other enterprises would serve the dual purpose of improving the country while employing those currently languishing without work.

In addition to fiscal stimulus, the government could start a public jobs program. A new Works Projects Administration would serve the same basic function as the fiscal stimulus, but with public jobs instead of private jobs. Like the fiscal stimulus, the number of unemployed people would decline, useful public projects would be completed, and the incomes paid out to those employed by the project would be spent, increasing aggregate demand.

The last idea that I will mention here is the possibility of a work-sharing policy. Although the best time to implement a work-sharing policy has passed, it still could be called upon to provide some relief to the ranks of the unemployed. Under a work-sharing policy, instead of a firm laying off, say, 10 percent of its workforce, it reduces the hours of each of its employees by 10 percent. This kind of policy has been successfully put into use in Germany during the recession. In the German approach to work-sharing, the hours are cut as mentioned above, and the burden of those lost hours are shared among the government, the employer, and the workers. The government replaces some of the income; the firm replaces some of it; and, the worker foregoes the rest.

Of course, implementing any of these policies would require that the government actually care about the high rate of unemployment which does not appear to be the case. The government certainly should be concerned about unemployment if not for moral reasons than for practical ones. High unemployment rates cause the government to spend significant amounts of money on welfare programs like unemployment insurance and food stamps. The amount it might spend employing those people would probably be more, but at least it would lead to the production of useful things, something welfare does not.

Instead of focusing on this however, both the President and the Congress have been almost exclusively trying to work out just how much the elderly, the poor, and the disabled will pay in order to reduce a budget deficit that they did not cause. With the government uninterested in their plight and very few job openings available, the unemployed truly have reached a point where they have nowhere to turn.