Having a college degree delivers relative economic advantages. In most cases, job applicants with college degrees will receive more consideration and priority than those without them. Consequently, college degree holders capture more of the limited stock of good jobs than their non-degreed peers, and therefore receive higher compensation. Problematically, many individuals — upon observing that college degree holders make more — conclude that if we could just get more people into college, our problems with low incomes and poverty would be solved. This is fundamentally wrong.

The first error advocates of this solution make is purely conceptual. They do not understand that college degrees primarily endow their recipients with positional advantages in the job market. That is, having a college degree gives individuals a better chance at capturing one of the (basically) scarce high-paying jobs. In aggregate though, it is the total number of high-paying jobs that matters. Contrary to what appears to be the popular belief, when a college degree is awarded, a new high-paying job does not just pop into existence.

In other words, the college solution does not scale. The advocates of the college solution observe that college graduates do better, and then conclude that if everyone graduated college, everyone would do better. This is a bit like observing that people who camp out a week early get front row tickets to the concert, and then concluding that if everyone camped out a week early, everyone would get front row tickets. Of course, the number of people who can get front row tickets is actually constrained by the number of front row seats, not by how many people camp out a week early.

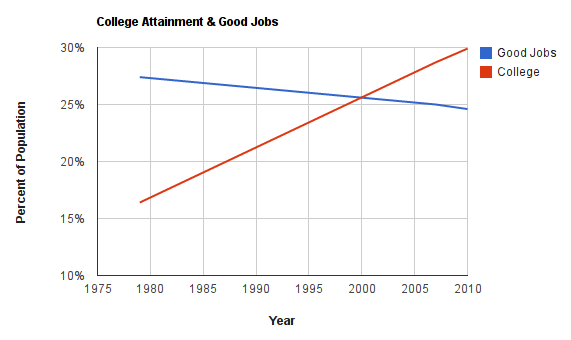

The same is true of good jobs: pushing more and more people into college wont necessarily alter the shape of the labor market in a way that generates more good jobs. Consider, for example, the last 31 years in America:

Using the recent CEPR report on good jobs and Census data on educational attainment, we can take a rough look at what happens when educational attainment shoots up. In 1979, 16.4 percent of Americans had college degrees and 27.4 percent had good jobs (defined as jobs that pay the real median male wage of 1979 and have health and retirement benefits of some sort). In 2007 — just prior to the recession — 28.7 percent of Americans had college degrees while only 25 percent had good jobs. So, even as the percentage of the population with college degrees nearly doubled, the percentage of the population with good jobs actually declined.

We can expect the disconnect between college and the number of good jobs to continue as well. As Doug Henwood pointed out in Left Business Observer 134, the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that only 5 of the 30 fastest-growing occupations in the next decade will require an associate degree or higher. There is no reason to think that cramming more people through college will change that landscape: the labor market demands what the labor market demands, not what increasing numbers of college graduates hunting for jobs would like it to.

This is not an insignificant statistical point either. It seems like most people in the United States buy into the notion that the road to more good jobs, less inequality, and less poverty runs through college. Speaking in aggregate, that’s just false. Everyone — education reformers, student movement people, and so on — needs to get that through their heads; otherwise, they will continue barking up the wrong tree. The college solution is a convenient social myth — it takes heat off the real problem of income and wealth distribution — but it is a myth still.

That is not to say that college education is socially useless. College education delivers all sorts of benefits, and is profoundly important (both socially and individually) in many ways. It is just totally irrelevant to economic justice discussions about good jobs, poverty, and inequality. And we should start treating it as such.