When I wrote the Family Fun Pack 3 years ago, I was interested in not just proposing a suite of child benefits for the US, but also in writing a paper that was based in a certain kind of universalist welfare state theory that you rarely see in think tank papers. The norm for think tank writing is to lay out a proposal and then produce some statistics on how many people it will help, what impact it will have on income, consumption, earnings, and things of that nature. I chose instead to walk the reader through the basic egalitarian logic behind child benefits and just let that stand as my argument for the policy proposals.

This argument goes like this:

1. Capitalist economies distribute incomes to individuals through factor payments to labor and capital.

2. Children don’t work and don’t own anything and so they cannot receive any individual income from factor payments.

3. Children typically live with other people, generally their parents, who receive factor payments. But relying on parents to stretch their personal factor payments across themselves and their children runs into two big problems that generate huge inequality, poverty, and financial instability.

3a. The first problem is that identical families with different numbers of children end up with vastly different incomes and standards of living. On a per-person basis, a single adult living alone ends up with 4 times as much income as an adult who earns the same amount of money as them but has 3 children to support.

3b. The second problem is that peak fertility is in the mid-to-late 20s while peak earning potential is in the mid-to-late 40s. This mismatch of fertility and earnings across the lifecycle means that people typically receive their highest level of income when they least need it and their lowest level of income when they most need it.

4. These two problems can be solved by levying broad-based taxes applied to all individuals and then using the revenue to provide benefits specifically to children. This directly solves the problem identified in (2) because it gives children a source of income, something the capitalist market does not give them. By doing this, you also end up solving the family-level problems identified in (3a) and (3b) because general taxes to fund child benefits results in net transfers away from families with fewer children and to families with more children and results in net transfers away from families with older workers in their peak earnings years and to families with younger workers in their early low-earning years.

As noted already, this is just a recitation of basic welfare state theory. It’s not even unique to child benefits. Benefits for the elderly, the disabled, and the unemployed function exactly the same way and are needed for exactly the same reasons.

What welfare state theorists realized many years ago was that, in addition to the inequalities caused by the capital/labor income split and the inequalities caused by different jobs receiving different wages, there are also inequalities caused by different families having different numbers of dependents. Thus, even if you made it so that workers received 100% of all factor payments (meaning capital’s share was reduced to nothing) and you made it so that all workers received the exact same wage, you would still wind up with an extremely unequal society unless you also installed a welfare state that transferred income from workers to nonworkers and thus to families with low numbers of dependents to families with high numbers of dependents.

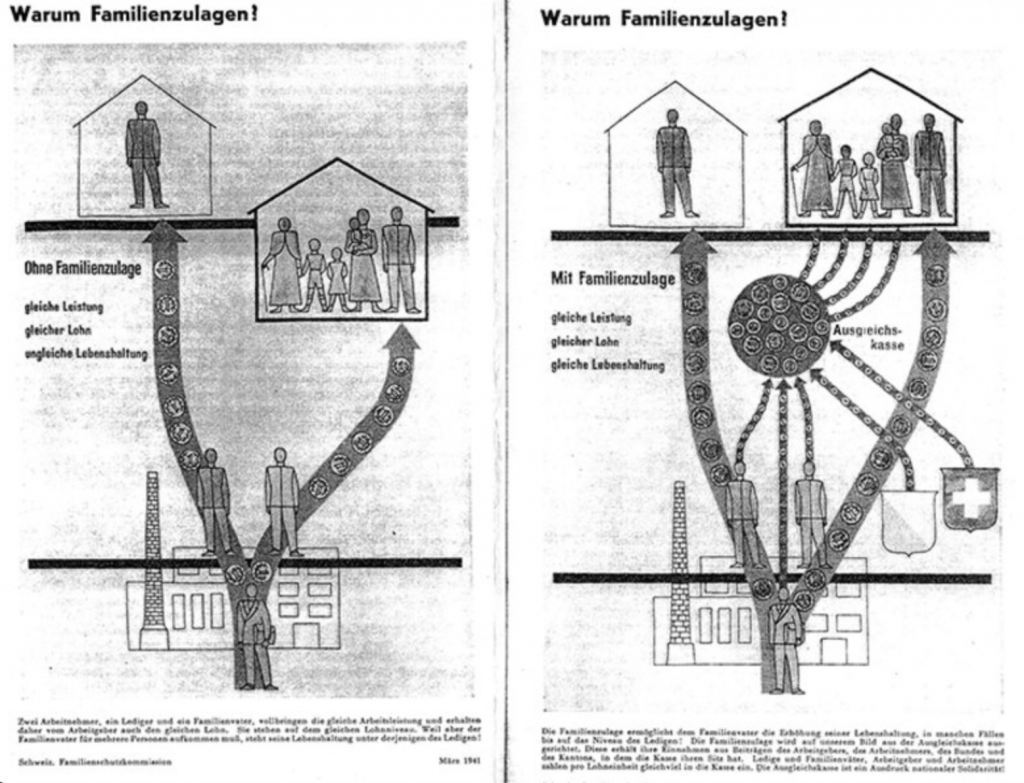

We see this dynamic clearly in this 1940s Swiss welfare state graphic below.

In these two panels, you have two workers who receive the same wage. One lives alone while the other lives with an elderly parent, three kids, and a spouse who just had a baby. In the first panel, there is no welfare state, and so the worker who has 5 dependents ends up with a much lower standard of living than the worker who has 0 dependents, this despite the fact that they receive the exact same wage. In the second panel, there is a welfare state, and so there are taxes on both workers that are then parceled out to the dependents. This results in a net transfer from the one-person family to the six-person family, which brings the living standard of the six-person family up to the level of the one-person family.

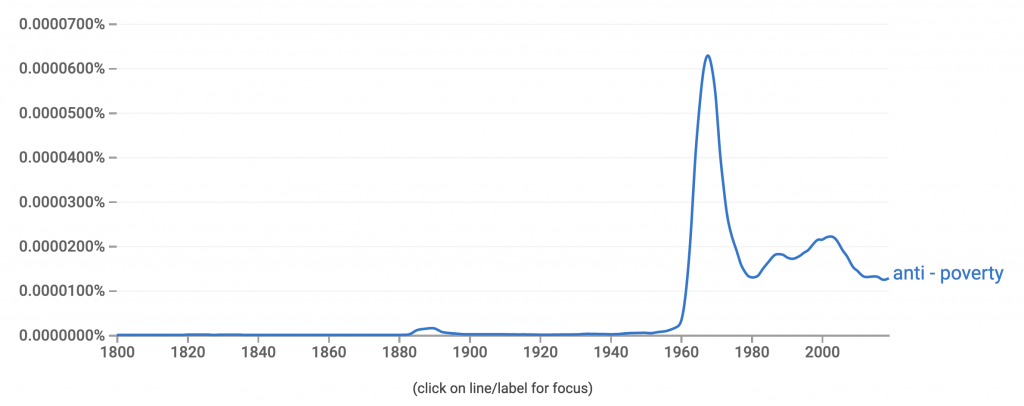

Although this presentation of the welfare state is very basic, it’s also something you see rarely in the public discourse, especially in the last few decades. I don’t know why this is exactly. I have a bit of a crank theory that says that Michael Harrington is to blame because, immediately following the publication of his 1962 book The Other America, we see a shift in interest towards “anti-poverty” programs, including LBJ’s 1964 War On Poverty.

The idea that the welfare state is about getting resources to poor people instead of about getting resources to nonworkers and smoothing out interfamily inequalities has become so prevalent in the discourse that my old-school presentational approach in the Family Fun Pack seems to have left some baffled or even scandalized.

Those scandalized don’t seem to object to the policy proposals, but sometimes become livid at the fact that the paper says that these proposals generate equality because they net transfer from those with fewer children to those with more. This anger seems to be rooted in some kind of culture war thing about having children. I am not sure what exactly to say to those people. Benefits like free child care, K-12 education, free health care for children, and a child allowance do involve net transfers from families with fewer children to families with more. Just like old-age pensions transfer from families with fewer elderly people to families with more elderly people and disability benefits transfer from families with fewer disabled people to families with more.

These kinds of net transfers are not an incidental characteristics of these programs: they are the primary mechanism by which they reduce inequality.