Since Romney admitted earlier this week that his tax rate is around 15% because his income is primarily from capital gains, the capital gains tax debate has fired up again. The traditional argument for a low capital gains tax is that it is necessary to encourage investment, but this argument is not well-supported.

When people invest, they essentially trade-off current consumption for greater future consumption. Investing $1 at 5% interest requires that I forego $1 of consumption right now in favor of $1.05 of consumption later. By taxing the $0.05 return on the investment, the trade-off becomes less desirable. If there were a 20% capital gains tax, then instead of trading $1 of present consumption for $1.05 of future consumption, I would be trading $1 of present consumption for $1.04 of future consumption because $0.01 of the return would be captured by the tax. According to theory, there are at least some marginal investors who would be willing to make the trade for $1.05 of future consumption, but not for $1.04 of future consumption. As we increased the tax rate higher and higher, more and more investors would be unwilling to invest for smaller and smaller returns. Thus, higher capital gains taxes lead to under-investment, which is something we want to avoid.

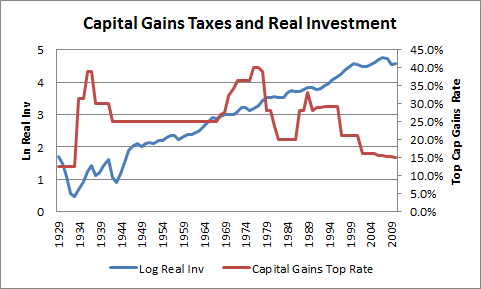

Or so the theory goes. The problem is that the empirical research on the matter does not exactly support this view. Jared Bernstein plotted the historical capital gains tax rate and the historical level of real investment on the same graph to see if there was any clear relationship. It turns out there is not:

Brad Plumer has a good round-up of studies and expert quotes that basically confirm this view. In addition to the empirical debunking, even the armchair speculation of the economist on the psychology involved here seems off to me. When people actually invest, do they contemplate it as a trade-off between current and future consumption? Investors are of course diverse; so, it is plausible that there are at least a few who do so. But, I have a hard time imagining that most investors make the kind of mental calculation that the economists claim they do.

Consider the type of investment that a great number of Americans do: investing for retirement. Those earning middle-incomes and higher often put some of their earnings into IRAs, 401Ks, or other kinds of investment vehicles to save for retirement. However, these kinds of investors do not even pay capital gains taxes. Instead, their taxes are deferred until they retrieve the invested money, which is then taxed as ordinary income. Even those who invest mainly for retirement in ways that are subject to the capital gains taxes do not seem likely to be that concerned with the tax. Although we can describe the behavior of these investors as constituting a trade-off between current consumption and future consumption, it seems like they internally understand it as a trade-off between current consumption and future economic security. They are not putting away money so that they can have even more at a future date. They simply want to have money to access in their older years, however much that might be. Unless the capital gains tax got exorbitantly high, it is hard to imagine that the typical worker investing for retirement will be dissuaded from doing so.

What about very wealthy individuals who are investing for reasons other than retirement? There are two reasons even these individuals do not seem like they would be dissuaded by anything but an exorbitant capital gains tax. Some of these investors — like Romney — clearly just want to live off their capital gains. They finance their living expenses solely off of returns on investments. The trade-off for them then is not entirely present consumption for future consumption; it is also a trade-off between working and not working. If they liquidate their investments and spend all their money, they cannot live off of capital gains, and would have to actually work, something they do not want to do.

Additionally, those with very high incomes also get low marginal utility out of much of their money. After the 15th sports car, buying a 16th is more a hassle than a welfare-enhancing improvement. At some point, more marginal consumption is just not worth it, and it makes more sense to put the money away for a future date at whatever return is available. Capital gains taxes then would not dissuade these kinds of investors.

Other investors want to leave money for their children, enjoy playing the stock market game, and have all sorts of other psychological motivations. Sure, a 99% capital gains tax would probably tamp down on all of the aforementioned kinds of investment, but it is not at all clear — empirically or speculatively — why increasing the capital gains tax modestly (for instance, to make it match the income tax) would drastically reduce investment. Yet, the tax policy of the right-wing is defended on the assumption that it will. Given that this assumption is provably false, the usual speculations about real motivations seem worth discussing: low capital gains taxes are massive giveaways to the wealthiest in our society, the constituency conservatives have traditionally served. Capital gains after all are the number one contributor to rising inequality in the United States.